Air France is right on the law in this recent Fifth Circuit decision (written by Judge Fortunato P. Benavides), but woefully wrong on the public relations front. In not settling the case, Air France has given an enterprising advertising firm for one of Air France’s competitors the basis for an effective “we’d never do this to you” advertising campaign against the airline.

Air France is right on the law in this recent Fifth Circuit decision (written by Judge Fortunato P. Benavides), but woefully wrong on the public relations front. In not settling the case, Air France has given an enterprising advertising firm for one of Air France’s competitors the basis for an effective “we’d never do this to you” advertising campaign against the airline.

Here’s what happened. Air France charged Edo Mbaba a $520 excess baggage fee for the four extra bags he took on his trip from Houston to Lagos. That was no problem, but when Mbaba flew through Paris, the flight was delayed and he missed his scheduled connection. As a result, he had to spend the night in the terminal and reclaim his baggage.

The next day, when Mbaba went to check his bags with Air France again for his flight to Lagos, Air France inexplicably advised him that he would have to pay another $4,000 in excess baggage fees. Thinking much as I would if confronted with such a demand, Mbaba requested that Air France simply return his luggage to Houston, which prompted the Air France personnel to inform Mbaba that if he didn’t quit griping and pay the four grand fee, they would take his luggage outside and barbecue it. Mbaba paid the fee, but then sued Air France in Texas for breach of contract and other state law claims.

Alas, the U.S. District Court and the Fifth Circuit concluded that Mbabaís claims are preempted by the Warsaw Convention. Nevertheless, here’s hoping that some of Air France’s competitors pick up on the decision and use it in the advertising wars so that the few bucks that Air France saved by stiffing Mbaba becomes an expensive lesson on how not to treat customers. Hat tip to Robert Loblaw for the link to the Fifth Circuit decision.

Daily Archives: July 26, 2006

Harvey Miller takes one on the chin

As noted in this previous post, former Weil, Gotshal & Manges bankruptcy partner and current Greenhill & Co. investment banker Harvey Miller is arguably the most leader of the movement over the past 30 years to elevate the compensation of corporate reorganization lawyers to levels commensurate with that of other corporate and securities lawyers. In so doing, Miller was not accustomed to losing many disputes over his firm’s fees in big reorganization cases, but — as the Wall Street Journal’s ($) Nathan Koppel reports here — Miller absorbed a hit on his fees as an investment banker earlier this month that could be the largest in the history of US corporate reorganizations.

As noted in this previous post, former Weil, Gotshal & Manges bankruptcy partner and current Greenhill & Co. investment banker Harvey Miller is arguably the most leader of the movement over the past 30 years to elevate the compensation of corporate reorganization lawyers to levels commensurate with that of other corporate and securities lawyers. In so doing, Miller was not accustomed to losing many disputes over his firm’s fees in big reorganization cases, but — as the Wall Street Journal’s ($) Nathan Koppel reports here — Miller absorbed a hit on his fees as an investment banker earlier this month that could be the largest in the history of US corporate reorganizations.

Based on a July 21 ruling of New York Bankruptcy Judge Robert Drain, Miller’s employer — New York investment bank Greenhill & Co. — must return $4.6 million of the more than $11 million the firm was paid as an adviser to Loral Space & Communications Ltd. in the satellite company’s chapter 11 case. Judge Drain concluded that Greenhill had improperly claimed a bonus for advising Loral in its 2003 bankruptcy and that Greenhill’s retention agreement did not authorize such a bonus. Greenhill was allowed to retain the $7 million balance of its compensation.

As noted in the previous post, my sense is that Miller and attorneys at the Akin, Gump law firm are not going to be exchanging holiday greeting cards any time soon.

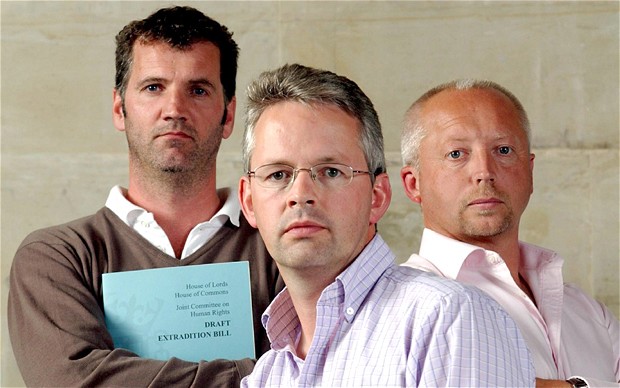

The Spokesman for the NatWest Three

What do you do when you can’t hang out and chat with your blokes?

What do you do when you can’t hang out and chat with your blokes?

Well, in the case of David Bermingham — one of the three former London-based National Westminster Bank PLC bankers dubbed the “NatWest Three” in the lexicon of Enron criminal cases — he sits for this interesting interview with the Chronicle’s Tom Fowler.

Although he does not reveal how he and his co-defendants intend to defend against the prosecution, Bermingham tells the story of how he and his NatWest colleagues — Gary Mulgrew and Giles Darby — voluntarily went to the UK equivalent of the SEC in November 2001 upon learning through news reports that a transaction in which they and NatWest Bank were involved had become part of the fraud investigation of former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow and his right-hand man, Michael Kopper.

Subsequently, the UK authorities passed along the information provided to them by Bermingham and his mates to the SEC and, the next thing you know, Bermingham, Mulgrew and Darby are the subject of a criminal complaint in Houston.

No US investigator contacted Bermingham, Mulgrew or Darby to get their side of the story before firing off the criminal complaint against them, but — as Bermingham notes — the Enron Task Force probably viewed the three bankers as pawns in their effort to put pressure on Fastow. After Fastow copped a plea, the Task Force was stuck with its dubious decision to prosecute the three UK citizens.

Although not well-reported in the press yet, the case against the NatWest Three is fairly straightforward, at least as Enron-related criminal cases go.

The Task Force alleges that the three defrauded their former employer by conspiring with Fastow and Kopper to underpay NatWest for its interest in an entity named Swap Sub, an affiliate of LJM1, the Fastow/Kopper-managed special purpose entity that was created in 1999 to hedge Enron’s valuable but highly volatile interest in a technology company called Rhythms.

Fastow arranged to have an entity called Southhampton that was owned by his family, Kopper and several other Fastow underlings at Enron (including Ben Glisan) buy NatWest’s interest in Swap Sub in March, 2000 for $1 million, which was substantially more than NatWest had that interest valued at the time.

After NatWest sold out, Fastow sold a portion of the old NatWest interest in Swap Sub through Southhampton to the three bankers personally for $250,000. About a month and a half later, Fastow and Kopper arranged to have Enron and Swap Sub unwind the hedge on the Rhythms stock, which resulted in Enron purchasing a large chunk of Enron stock from Swap Sub. The NatWest Three’s net share of the Enron stock sales proceeds was $7.3 million.

In short, the Task Force alleges that the NatWest Three’s making $7.3 million on an investment of $250,000 a month and a half earlier violates the “too good to be true” rule.

Presumably, Fastow and Kopper are prepared to testify that the NatWest Three knew that Fastow and Kopper had arranged with Enron to unwind the hedge on Rhythms stock with Swap Sub, knew that such unwinding would make Swap Sub worth much more than NatWest had it valued at the time, and that neither Fastow nor the NatWest Three disclosed the situation to NatWest before the bank sold its interest in Swap Sub to Southhampton for a measly $1 million.

For their part, Bermingham, Mulgrew and Darby contend that they knew nothing about Fastow and Kopper’s plan to unwind the Rhythms hedge with Enron, that the $1 million price that Southhampton paid for NatWest’s interest in Swap Sub was substantially more than it was worth at the time, that the $250,000 price they paid for an interest in Swap Sub was similarly reasonable given the risk of the investment, and that they were as pleasantly surprised as anyone on the big return on their investment when Enron and Swap Sub unwound the hedge a month and a half later (remember, all this took place before the bursting of the stock market bubble on tech stocks).

Interestingly, despite the fact that all of the foregoing information has been well-known to NatWest for several years now, the bank did not pursue either a civil case or criminal prosecution of the NatWest Three in the UK.

By the way, colorful Houston-based criminal defense attorney Dan Cogdell, who successfully defended former Enron in-house accountant Sheila Kahanek in the Nigerian Barge case, is defending Bermingham. Cogdell’s involvement ratchets up the entertainment value of any case, so stay tuned.