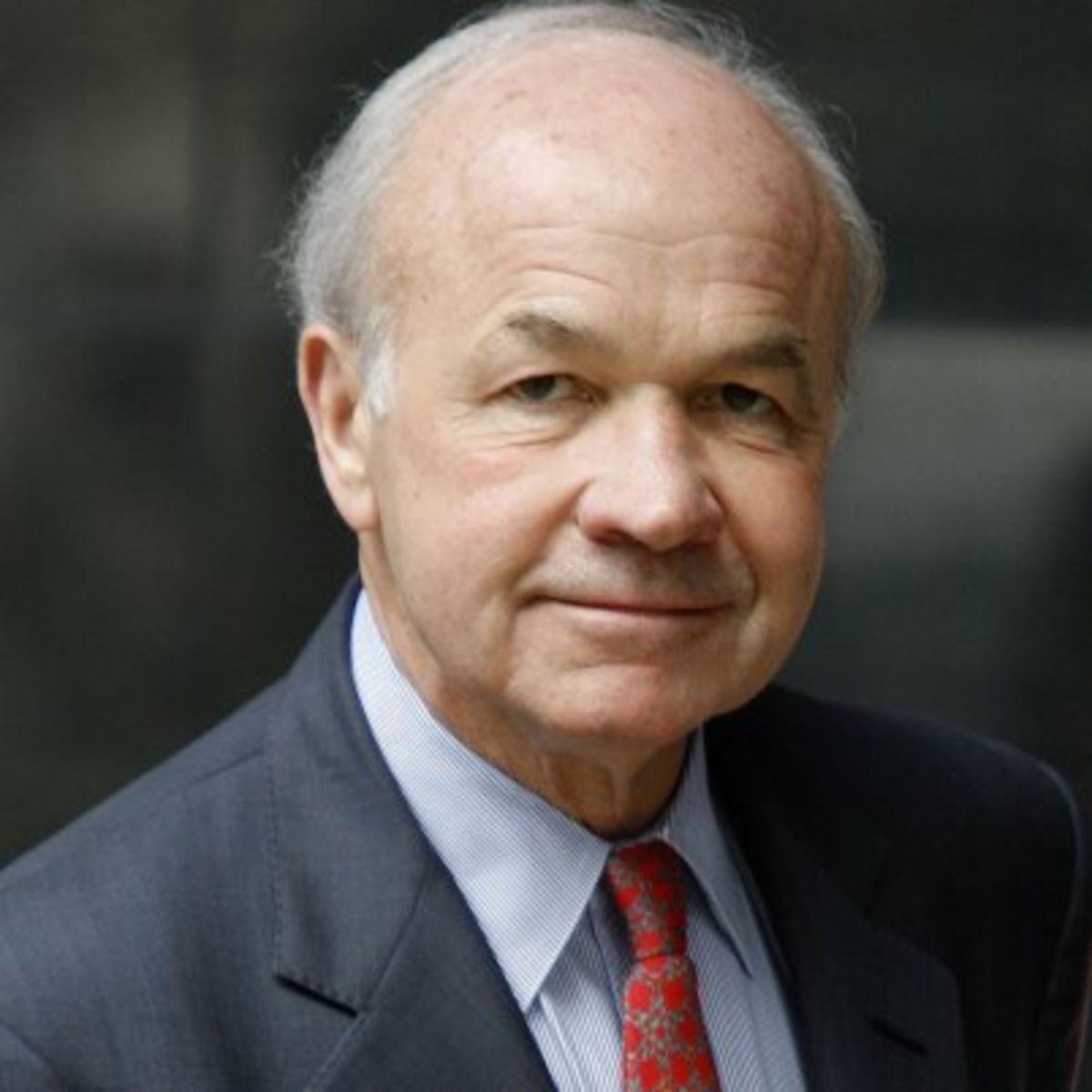

Former Enron chairman and CEO Ken Lay died yesterday of a heart attack. Given the stress that Mr. Lay had endured over the past five years, such a fate is certainly not surprising.

Former Enron chairman and CEO Ken Lay died yesterday of a heart attack. Given the stress that Mr. Lay had endured over the past five years, such a fate is certainly not surprising.

However, my sense is that the heart attack was merely the physical manifestation of what really killed this proud, talented, and flawed man — his inability to overcome the Enron Myth and the societal implications of it.

By now, we all know the myth — Enron was merely an elaborate financial house of cards hidden from innocent and unsuspecting investors and employees by a deceitful management team led by the greedy and lying Mr. Lay.

The Enron Myth is so thoroughly accepted that otherwise intelligent people reject any notion of ambiguity or fair-minded analysis in addressing facts and issues that call the morality play into question. The primary dynamics by which the myth is perpetuated are scapegoating and resentment, which are exhibited everywhere:

The Houston Chronicle’s business columnist ridiculing Mr. Lay and calling for his conviction on almost a daily basis throughout the trial;

The community outpouring of celebration over the guilty verdict against Mr. Lay and the self-righteous indignation over his continued claim that he committed no crimes;

A Houstonian interviewed on radio yesterday contending that she was unsatisfied because Mr. Lay’s death had allowed him to escape appropriate punishment;

A prominent Houston-based blogger mocking Mr. Lay’s death (here and here);

Without a smidgen of evidence, a Houston criminal defense attorney suggesting during an interview on MSNBC yesterday that Mr. Lay may have committed suicide to void his conviction.

These are but a few examples of the frequent eruptions from the cauldron of societal bitterness over Enron that are palpable reminders of the fragile nature of civil society.

The Enron Myth conveniently serves to obscure that which most people do not want to confront. Loss, fear, and anger expose our essential human insecurity — Christians sometimes refer to it as our “brokenness.” The vulnerability that underlies such insecurity is scary to behold, so we use myths and the related dynamics of scapegoating and resentment to distract us.

Therefore, a wealthy and powerful businessman who is easy to resent becomes a handy scapegoat. We rationalize that he did bad things that we would never do if placed in the same position and thus, he is deserving of our punishment. That the scapegoat is portrayed as greedy and arrogant — just as we are — makes the lynch mob even more bloodthirsty as it attempts to purge collectively that which is too sordid for its members to face individually.

As noted in this prior post, even the Task Force prosecutors have admitted that the legal case against Lay was extraordinarily weak. But the power of the Enron Myth and the real presumption in the criminal case against Mr. Lay are such that even presumably fair-minded jurors dispense with critical thinking skills when confronted with supposedly the biggest business conspiracy in the history of federal prosecutions.

Rather than seeking the truth regarding that alleged mass conspiracy, the jurors were content with a prosecution that cast Mr. Lay as a liar about Photofete and his company line of credit, and ignored the paucity of evidence of any alleged massive conspiracy or even the true reasons why Enron collapsed. The myth is so pervasive and accepted — why bother with the truth?

The carnage of the Enron Myth and similar myths is now stacked high — the destruction of Arthur Andersen, the vapid Enron-related Congressional hearings, the shallow Enron documentary, Martha Stewart, Jamie Olis, Daniel Bayly, William Fuhs, Frank Quattrone, Hank Greenberg, Mr. Lay’s co-defendant Jeff Skilling (see also here), the NatWest Three — the list goes on and on.

In the wake of such destruction of wealth and lives, the public is even less willing to confront the vacuity of the myth and the destructive dynamics by which it is perpetrated. In fact, any challenge to the myth is now commonly met with derision and appeals to even more resentment over the Enron failure.

Such syndromes are not only an abuse of our justice system. They are also a serious affront to civil society. Ken Lay was no criminal. Did he fudge the truth? Maybe. But even if so, did his lies justify public humiliation, a physically-draining criminal trial, and a life prison sentence?

Not in a truly civil society.

Ken Lay’s sudden death is a terrible tragedy for his family and friends. My family’s thoughts and prayers are with them.

But the larger tragedy is that a myth has again played out as “justice” in our criminal justice system while distracting us from examining what really happened at Enron, understanding the benefits and risks of such a company, and educating ourselves on how to take advantage of such benefits while hedging those risks prudently.

Such a sober undertaking is not as easy as rationalizing a financial failure by calling a rich man a crook and reveling in his demise. But it’s far more likely to result in a better — and far more honest — understanding of investment and markets.

As well as ourselves.