With Shell Oil Company pulling out as the Houston Open’s title sponsor after a successful 26-year run, the Houston Golf Association finds itself in an all too familiar position — what must be done to make the venerable tournament something other than an afterthought among the numerous non-major PGA Tour events?

With Shell Oil Company pulling out as the Houston Open’s title sponsor after a successful 26-year run, the Houston Golf Association finds itself in an all too familiar position — what must be done to make the venerable tournament something other than an afterthought among the numerous non-major PGA Tour events?

Houston has a rich golf history, so there is considerable amount of civic pride involved in this question. But finding a title sponsor is no easy task — the price tag to sponsor an event such as the Houston Open is almost certainly in the $10 million range.

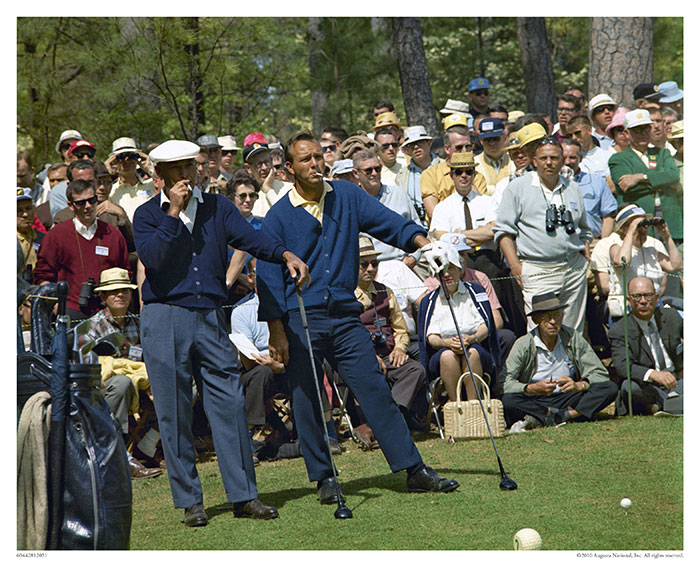

The first Houston Open was in 1922 and the tournament is tied with San Antonio’s Valero Texas Open as the third oldest non-major championship on the PGA Tour behind only only the Western Open (1899) and the Canadian Open (1904).

Despite that legacy, the tournament has periodically struggled. After the tournament was revived at River Oaks in 1946, the Houston Open became a regular Tour stop when it was played at Memorial Park Golf Course during the 1950’s and early 60’s, and then moved to Champions Golf Club in the late 1960’s for six years.

But the tournament wandered to several different area courses after its stint at Champions and its future seemed uncertain.

Indeed, after a particularly unfulfilling mid-1970’s tournament, the late Jack Gallagher, a crusty, old school golf columnist at the Houston Post, penned a column in which the basic thrust was “if this is the best the HGA can do, then why don’t we just forget about the whole damn thing.”

The Houston Golf Association recognized the dire circumstances and turned things around in 1975 by entering into a long term agreement with The Woodlands Corporation, which was in the early stages of developing a master-planned suburban community on the far north side of the Houston metro area.

For the next 26 years, the Houston Open and The Woodlands enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship as the golf tournament rode The Woodlands’ extraordinary growth to become one of the top tournaments on the PGA Tour in terms of money raised for charity each year.

That status was cemented when Shell stepped up in 1991 to become the stable title sponsor that the tournament had always lacked.

Unfortunately, by the late 90’s, the mutually-beneficial relationship between the HGA and The Woodlands Corporation was unraveling.

The HGA believed that the tournament needed to move from the Tournament Players Course in The Woodlands, which had parking problems and limited adjacent land to stage a Tour event.

Moreover, the tournament struggled with a date on the calendar a few weeks after The Masters, which is a time in the Tour schedule when many top players rest in preparation for the summer grind of the Tour.

After The Woodlands Corporation developed two outstanding courses at Carlton Woods Golf Club on the west side of The Woodlands, the HGA concluded that The Woodlands Corporation had reneged on a commitment to build a new TPC Course along Spring Creek on the west side of The Woodlands to host the Houston Open.

The Woodlands Corporation — which was owned by different owners than George Mitchell and his aides who had struck the original 1975 deal with the HGA — concluded that the HGA did not sufficiently appreciate how much The Woodlands had contributed to the success of the tournament and that The Woodlands really did not need the golf tournament to continue its success.

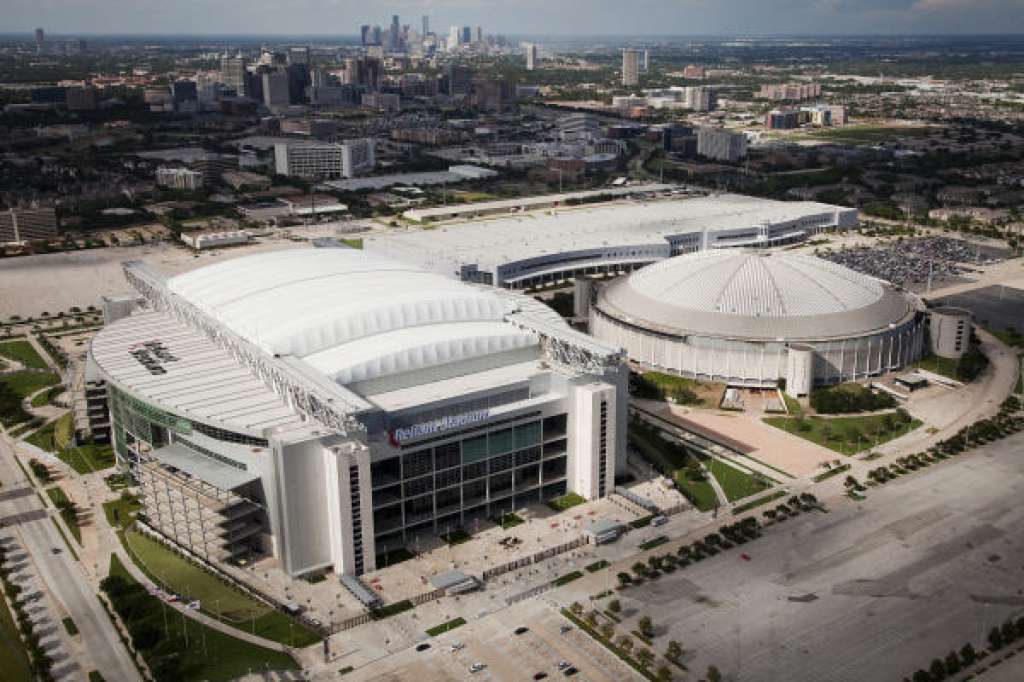

Consequently, in 2002, the HGA decided to leave The Woodlands and relocate to Redstone Golf Club (now Golf Club of Houston) in Humble on the northeast side of Houston.

The HGA struggled through three tournaments at Redstone’s Jacobson-Hardy Course (the renovated El Dorado Country Club course), which was not close to as good a tournament venue as the TPC in The Woodlands. Charitable donations to the tournament dipped and few of the top Tour pros played in those first tournaments at the new location.

Nevertheless, the scrappy HGA made the best of a bad situation.

In connection with the opening of the Rees Jones-designed Tournament Course at Redstone in 2006, the HGA persuaded the PGA Tour to give the Houston Open the weekend before the Masters as its permanent date. Then, the HGA groomed the Tournament Course to simulate conditions that the players would confront the following week at Augusta National during The Masters.

The result was that many top Tour players embraced the idea of playing tournament golf and practicing in Augusta-like conditions the weekend before the Masters. After a few years in its pre-Masters weekend date, the Houston Open was enjoying some of its strongest fields in its history.

Alas, prolonged success is elusive for the Houston Open. A year or so into the latest downturn in the energy industry, Shell announced that it was not renewing its title sponsorship for the tournament.

Meanwhile, the lack of a title sponsor tends to expose some of the other shortcomings of the tournament.

Although the HGA continues to do a great job of promoting the tournament with Tour players, the reality is that the Tournament Course is a rather boring, flat-land course built in the coastal plain of Texas that bears little resemblance to the hills of Augusta National.

Moreover, the Tournament Course is not fan-friendly. Although the course has some interesting holes, the routing of the course is an unmitigated disaster.

Sixteen of the course’s holes are separated from the 1st and 18th holes, the practice facilities, and the clubhouse by a half-mile walk along and over an unsightly drainage ditch. Because of that long trek, some fans at the tournament never venture beyond the 1st and 18th holes and the adjoining practice facilities.

Also, the Tournament Course is located far away from Houston’s quality hotels and other accommodations that attract Tour players and visitors to golf tournaments. Meanwhile, The Woodlands has developed the Houston area’s best destination resort, along with a beautiful downtown river walk area dotted with quality restaurants, entertainment venues, shops, and hotels.

One can only imagine how much the Houston Open would have benefited from close access to those amenities had the HGA and The Woodlands Corporation found a way to bridge their differences.

Perhaps those shortcomings are what prompted Houston Mayor Sylvestor Turner’s display of nostalgia at the tournament over this past weekend.

Apparently without consulting the HGA, Mayor Turner announced at the tournament that he thought that the Houston Open should return to Memorial Park Golf Course, which has not hosted a Tour event since 1963.

In making that announcement, Mayor Turner overlooked that Memorial Park GC has a tiny clubhouse, nominal practice facilities, virtually no driving range, and no place for public parking. It would require a multi-million dollar investment in improvements constructed over several years before Memorial Park GC could even be considered as a host for a Tour event.

The bottom line is that such an investment is not going to happen.

Which brings us back to the question — what is going to become of the Houston Open in its post-Shell crossroads?

Participation by top Tour players has lagged a bit in recent years, but this year’s tournament attracted four of the top 10 in the Official World Golf Rankings and 10 of the top 25. That’s comparable to what other Tour events generate that are not a major or a World Golf Association tournament.

And although the Tournament Course is not optimal, the reality is that there are few courses in the Houston area that have the combination of location, facilities, and accessible areas for public parking necessary to host a PGA Tour event.

And one of those is not Memorial Park GC.

With a workable date on the PGA Tour calendar and a serviceable golf course to host the event, my sense is that the HGA — which has been a wonderful steward of the tournament — will find another title sponsor (or multiple sponsors) to replace Shell and continue to hold the tournament at the Golf Club of Houston’s Tournament Course.

Sometimes maintaining a pretty good thing well is the best that can be done.