As noted in this previous post, the arrest in Louisiana of former University of Texas Health Science Center professor and physician Dr. Anna Pou on wrongful death charges for her actions in attempting to save lives during the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina is an egregious example of prosecutorial misconduct.

As noted in this previous post, the arrest in Louisiana of former University of Texas Health Science Center professor and physician Dr. Anna Pou on wrongful death charges for her actions in attempting to save lives during the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina is an egregious example of prosecutorial misconduct.

As is typical in such cases, word is now filtering out about the real motivations for the prosecution. Not only is an elderly Louisiana attorney general who campaigned on a plank of “cracking down on abuse of the elderly” at the center of the dubious decision to arrest, this NY Times article reports that Dr. Pou’s accusers are three employees of LifeCare Hospitals, the company that owned the facility where 24 out of 55 elderly patients died in the aftermath of Katrina and whose top administrator and medical director didn’t even show up at the hospital during those chaotic days. It turns out that the accusing LifeCare employees didn’t make any effort to evacuate the elderly and sick patients, either. Does this have the smell to you of someone attempting to distract attention (or perhaps avoiding prosecution) from their own indiscretions?

Dr. Kevin Pho of Kevin, M.D. is doing a good job of keeping up with the reactions and commentary around the web to the case against Dr. Pou and the nurses. The case against Dr. Pou is the other side of the same coin that the government flips when it criminalizes risk-taking by businesspersons, so stay tuned to developments in this troubling prosecution.

Category Archives: Health Care

Thinking about progress in health care

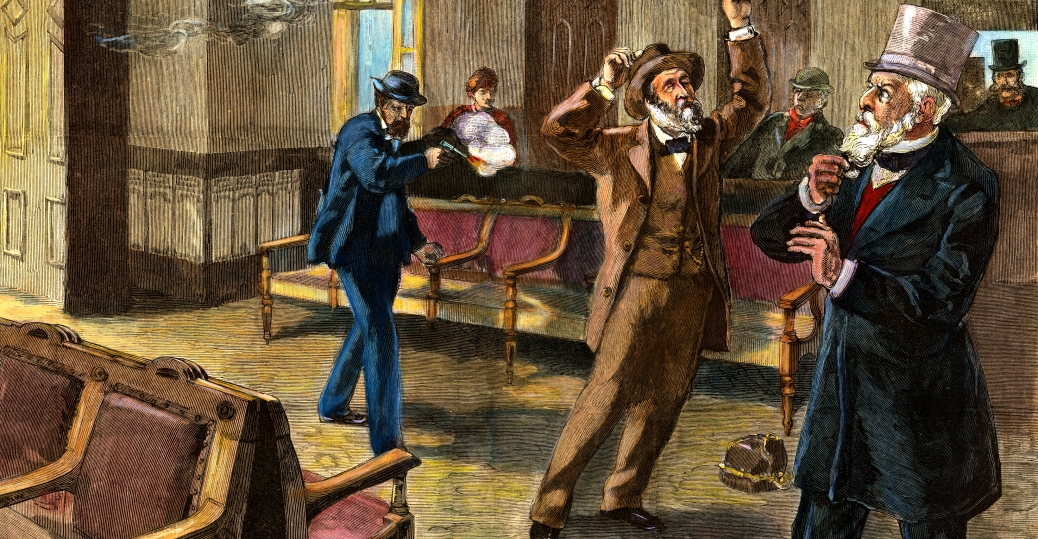

This NY Times article tells the fascinating story about the assassination of President James A Garfield in 1881 an exhibit commemorating the 125th anniversary of Garfield’s assassination at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

This NY Times article tells the fascinating story about the assassination of President James A Garfield in 1881 an exhibit commemorating the 125th anniversary of Garfield’s assassination at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

President Garfield was shot in Washington by a disgruntled federal job-seeker, Charles J. Guiteau, who made his move while Garfield was waiting for a train. What is not as well-known is that neither of the shots that hit Garfield should have fatal even by the more primitive medical standards of the 1880’s.

As my late father once observed to me in a discussion of Presidential assassinations, “Garfield’s assassin just shot him. Garfield’s doctors killed him.”

The Times article reminds me of another interesting medical case that Dr. Donald J. DiPette, chair of the Department of Internal Medicine at Texas A&M University Medical School, presented earlier this year during the annual Walter M. Kirkendall Lecture that the University of Texas Medical School conducts in honor of my father.

Dr. DiPette’s lecture was about how advances in clinical research on hypertension had contributed to our understanding and knowledge of related chronic illness. He used a case study of a man in his mid-50’s in the late 1930’s who was showing signs of acute hypertension as an example of how that understanding can change the world.

The negative impact of hypertension on an individual’s health was not well-understood in the late 1930’s and 40’s. Dr. DiPette showed how the patient’s health in the case study deteriorated at an accelerated rate as his blood pressure readings increased markedly from 1937 to 1945. One evening in early 1940, the subject in the study fainted at the dinner table. The patient’s doctors at the time were unsure why.

By 1945, the patient — who was still working in an important and high-pressure job — had blood pressure that was off the charts and was experiencing a combination of associated medical problems that would have landed him in a hospital these days.

Nevertheless, the patient continued to work and, a couple of months after a particularly important work-related meeting, the patient died of a massive stroke.

Most times, the subjects of medical case studies are anonymous. But at the end of his lecture, Dr. DiPette revealed the name of the subject of this particular case study — President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Dr. DiPette’s point was that President Roosevelt’s acute hypertension clearly affected his performance. Our lack of knowledge about hypertension in 1945 — which finally began to be better understood in the decade after FDR’s death — changed the course of the 20th century. That “important work-related meeting” that Dr. DiPette referred to was the Yalta Conference of early February 1945 that doomed Eastern Europe to over a generation of tyranny.

Remember that the next time you hear someone complain about the cost of advancing medical research.

Thinking About Performance-Enhancing Drugs

Mark Sisson is a Malibu-based former elite marathoner and triathlete who became well-known in athletic circles as an expert on drug testing for athletes while serving for 13 years as the anti-doping and drug-testing chairman of the International Triathlon Union and as the union’s liaison to the International Olympic Committee.

Mark Sisson is a Malibu-based former elite marathoner and triathlete who became well-known in athletic circles as an expert on drug testing for athletes while serving for 13 years as the anti-doping and drug-testing chairman of the International Triathlon Union and as the union’s liaison to the International Olympic Committee.

In a provocative letter to his friend Art DeVany, Sisson talks about drug-testing for athletes and makes some interesting observations:

At the risk of sounding a bit brazen, I would suggest to you and your audience that sport would be better off allowing athletes to make their own personal decisions regarding the use of so-called “banned substances” and leaving the federations and the IOC out of it entirely. (Even the term “banned substance” has a negative connotation, since most of these substances are actually drugs that were developed to enhance health in the general population). Bottom line: the whole notion of drug-testing in sports is far more complex than even the media make it out to be. [. . .]

The performance requirements set by the federations at the elite level of sport almost demand access to certain “banned substances” in order to assure the health and vitality of the athlete throughout his or her career and – more importantly – into his or her life after competition. . . . World class athletes tend to die significantly younger than you would predict from heart disease, cancer, diabetes and early-onset dementia. They also typically suffer premature joint deterioration from the years of pounding, and most endurance athletes look like hell from the years of oxidative damage that has overwhelmed their feeble antioxidant systems.

Most people don’t realize it, but training at the elite level is actually the antithesis of a healthy lifestyle. The definition of peak fitness means that you are constantly at or near a state of physical breakdown. As a peak performer on a world stage, you have done more work than anyone else, but you have paid a price.

It is again ironic that the professional leagues and the IOC — the ones who dangle that carrot of millions of dollars in salary or gold-medalist endorsements — are the same ones who actually created this overtrained, injured and beat-up army of young people. They don’t care. These organizations then deny the athletes the very same drugs and even some natural “health-enhancing” substances that the rest of society can easily receive whenever they feel the least bit uncomfortable. [. . .]

I believe that with proper supervision, athletes could be healthier and have longer careers (not to mention longer and more productive post-competition lives) using many of these “banned substances.” And perhaps the biggest assumption I will make here is that the public just doesn’t care. Professional sport has become theater. All the public wants is a good show and an occasional world record.

As I noted earlier with regard to Barry Bonds’ use of steroids, management of professional sports has not done a good job of drawing the line with regard to what should constitute illegal use of drugs, on one hand, and legal performance-enhancing substances that are beneficial to the health of the athletes, on the other.

As a result, the league rules (as well as our nation’s laws) governing which substances are legal and illegal are often arbitrary and hypocritical.

Indeed, professional sports teams (as well as their fans) often encourage their players to risk their health. Players who “play with pain” are the subject of adulation in all levels of sport, as are players who risk injury by running into walls, taking cortisone shots to be able to perform with reduced pain and undergoing risky surgeries to lessen pain in order to play in a big game (remember Curt Schilling in the 2004 World Series?).

The difference between a professional athlete taking pain-reducing drugs to get through a season and another athlete using performance-enhancing drugs in an attempt to be more productive during a season is not as wide as it may appear at first glance.

Thinking about heroin addiction

Theodore Dalrymple — the pen name of British psychiatrist and author, Anthony Daniels (previous posts here) — has written a new book, Romancing Opiates: Pharmacological Lies and the Addiction Bureaucracy (Encounter 2006) in which he challenges the conventional medical wisdom regarding opium addition. In this Wall Street Journal ($) op-ed, Dalrymple provides interesting insight into the nature of addiction:

Theodore Dalrymple — the pen name of British psychiatrist and author, Anthony Daniels (previous posts here) — has written a new book, Romancing Opiates: Pharmacological Lies and the Addiction Bureaucracy (Encounter 2006) in which he challenges the conventional medical wisdom regarding opium addition. In this Wall Street Journal ($) op-ed, Dalrymple provides interesting insight into the nature of addiction:

I have witnessed thousands of addicts withdraw; and, notwithstanding the histrionic displays of suffering, provoked by the presence of someone in a position to prescribe substitute opiates, and which cease when that person is no longer present, I have never had any reason to fear for their safety from the effects of withdrawal. It is well known that addicts present themselves differently according to whether they are speaking to doctors or fellow addicts. In front of doctors, they will emphasize their suffering; but among themselves, they will talk about where to get the best and cheapest heroin.

A real hero’s story

Following on this post from a couple of months ago on Virginia Postrel‘s donation of a kidney to a friend, don’t miss Virginia’s inspiring Texas Monthly ($) article on the experience.

Following on this post from a couple of months ago on Virginia Postrel‘s donation of a kidney to a friend, don’t miss Virginia’s inspiring Texas Monthly ($) article on the experience.

Interestingly, the most important part of Virginia’s successful donation was her stubborness in going through with it:

Most important, it turned out, I had the right personality. Donating a kidney isnít, in fact, a matter of just showing up. You have to be pushy. Unless youíre absolutely determined, youíll give up, and nobody will blame youóexcept, of course, the person who needs a kidney. When I went to see my Dallas doctor for preliminary tests, the first thing she said was ìYou know, you can change your mind.î

To me, giving Sally a kidney was a practical, straightforward solution to a serious problem. It was important to her but not really a big deal to me. Until the surgery was scheduledófor Saturday, March 4óand I started telling people about it, I had no idea just how weird I was.

Normal people, I found, have a visceralópun definitely intendedóreaction to the idea of donating an organ. Theyíre revolted. They identify entirely with the donor but not at all with the recipient. They donít compare kidney donation to other risky behavior, like flying a plane or running 31 miles to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and back, as my brother did last summer.

What a gal!

Diet and Alzheimer’s

A new Annals of Neurology study headed by Nikolaos Scarmeas of the Columbia University Medical Center in New York has found that people who followed a Mediterranean-style diet were up to 40% less likely than those who largely avoided it to develop Alzheimer’s during the course of the research study. Previous posts on Alzheimer’s research are here.

A new Annals of Neurology study headed by Nikolaos Scarmeas of the Columbia University Medical Center in New York has found that people who followed a Mediterranean-style diet were up to 40% less likely than those who largely avoided it to develop Alzheimer’s during the course of the research study. Previous posts on Alzheimer’s research are here.

The study evaluated about 2,200 elderly residents of northern Manhattan every 18 months for signs of dementia over a four years period. None showed any dementia at the start of the study, but by the end of the study, 262 had developed Alzheimer’s. The researchers gave each participant a score of zero to nine on a scale that measured how closely they adhered to a Mediterranean-style diet. Compared to those showing the lowest adherence, those who scored four or five on the diet scale showed 15% to 25% less risk of developing Alzheimer’s during the study and those with higher scores had about 40% less risk. Prior research suggested that certain components of the Mediterranean diet can reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s, but the research focused on specific nutrients (such as vitamin C) or foods such as fish. By incorporating an entire diet, the new study addresses possible interactions between specific foods and nutrients.

The diet tested in the study included primarily vegetables, legumes, fruits, cereals and fish, while limiting intake of meat and dairy products. The diet also included drinking moderate amounts of alcohol and emphasizing monounsaturated fats, such as in olive oil, over saturated fats. Previous research has suggested that such an approach also reduces the risk of heart disease, and the new study is additional evidence that certain conditions that are associated with heart disease — high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, smoking and uncontrolled diabetes — may also contribute to Alzheimer’s.

Houston’s Bubble Boy

You may want to set your Tivo to this Friday at 1 p.m. when local PBS channel KUHTDT-TV (check your local PBS station for the time) will rebroadcast the excellent PBS American Experience series segment that ran last night entitled The Boy in the Bubble, which focuses on the difficult ethical issues raised by the medical treatment of the late Houstonian David Vetter (a/k/a the “bubble boy”), who had severe combined immunodeficiency and lived inside a sterile plastic chamber for his 12 year life:

You may want to set your Tivo to this Friday at 1 p.m. when local PBS channel KUHTDT-TV (check your local PBS station for the time) will rebroadcast the excellent PBS American Experience series segment that ran last night entitled The Boy in the Bubble, which focuses on the difficult ethical issues raised by the medical treatment of the late Houstonian David Vetter (a/k/a the “bubble boy”), who had severe combined immunodeficiency and lived inside a sterile plastic chamber for his 12 year life:

When David Vetter died at the age of 12, he was already world famous: the boy in the plastic bubble. Mythologized as the plucky, handsome child who had defied the odds, his life story is in fact even more dramatic. It is a tragic tale that pits ambitious doctors against a bewildered, frightened young couple; it is a story of unendingly committed caregivers and resourceful scientists on the cutting edge of medical research. This American Experience raises some of the most difficult ethical questions of our age. Did doctors, in a rush to save a child, condemn the boy to a life not worth living? Did they, in the end, effectively decide how to kill him?

Here is a Steve McVicker/Houston Press story from nine years ago that raises many of the same questions as those addressed in the PBS show.

Inhibiting the production of vaccines

The ever-observant Walter Olson points us to this interesting Theodore Dalrymple review of the new book The Cutter Incident: How Americaís First Polio Vaccine Led to the Growing Vaccine Crisis (Yale University Press 2005) by Paul Offit, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania.

The ever-observant Walter Olson points us to this interesting Theodore Dalrymple review of the new book The Cutter Incident: How Americaís First Polio Vaccine Led to the Growing Vaccine Crisis (Yale University Press 2005) by Paul Offit, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Offit’s book tells the story of how a heartbreaking disaster caused by mass immunization during research ó a disaster that helped lead to the major medical and scientific breakthrough of virtually eliminating polio from much of the world — led to a legal ruling that has subsequently inhibited pharmaceutical companies from developing and manufacturing vaccines. During the early stages of polio immunization, the Cutter Company followed the then-imperfect instructions regarding production of the vaccine to the letter, but those instructions — together with the then-imperfect scientific knowledge regarding the vaccine — proved inadequate to guarantee the vaccineís safety. As a result, the live polio virus survived in some of the company’s vaccine, which was distributed to a large number of people. Seventy thousand of those immunized by the faulty vaccine experienced the transient flu-like symptoms of mild polio, 200 wound up being paralyzed by polio, and 10 died from the disease.

A real hero

While enduring Andy Fastow’s explanations this past week on how he was a hero at times while working at Enron, I’ve been meaning to note the story of a real hero, Dallas-based blogger and writer, Virginia Postrel.

While enduring Andy Fastow’s explanations this past week on how he was a hero at times while working at Enron, I’ve been meaning to note the story of a real hero, Dallas-based blogger and writer, Virginia Postrel.

Check out Virginia’s posts here, here and here for the story.

What a gal!

Belly to Hip Ratio more important than BMI?

This Washington Post article reports on a new study published in The Lancet that indicates the relationship between belly size and hip size is more useful measure of health risk than the commonly-used body mass index (BMI):

This Washington Post article reports on a new study published in The Lancet that indicates the relationship between belly size and hip size is more useful measure of health risk than the commonly-used body mass index (BMI):

According to a study published in The Lancet, a calculation comparing waist circumference to hip circumference is a better predictor of heart attack risk than . . . [b]ody mass index, [which] is often used to screen for obesity and to assess risk for a variety of diseases and conditions, including diabetes, metabolic syndrome and heart attack.

[T]he Lancet study, described by the authors as the largest and most conclusive to date, found that “BMI is a very weak predictor of the risk of a heart attack,” said Salim Yusuf, lead author and director of the Population Health Research Institute at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “Measuring the girth of the waist and [the] girth of the hip is far more powerful.”

The authors suggested people forgo calculating BMI. “I’d say just do the waist-to-hip ratio,” Yusuf said. “There really is no additional value [in] doing the BMI.”

The study indicates that even relatively lean people with a BMI that is quite low still have increased risk for heart attack based on the presence of abdominal fat. It remains unclear why location of fat in the abdominal area poses a greater health risk than fat carried around the hips, but recent studies have also linked waist-to-hip ratio to increased risk of diabetes and hypertension. The findings reported in Lancet study indicate that men with waist-to-hip ratios greater than 0.95 are at heightened risk for a heart attack and that females with ratios above 0.8 are at increased risk, and that the the risk “rose progressively with increasing values for waist-to-hip ratio, with no evidence of a threshold.”

Speaking of health-related matters, the Chronicle has added a health-related blog by medical reporter Leigh Hopper to its growing list of weblogs. Chronicle technology reporter Dwight Silverman spearheaded the Chronicle’s blog initiative last year, and now other prominent newspapers are emulating the Chronicle’s blog idea. Kudos to Dwight and the Chronicle for contributing greatly to this productive trend of enhancing communication between media and its customers.