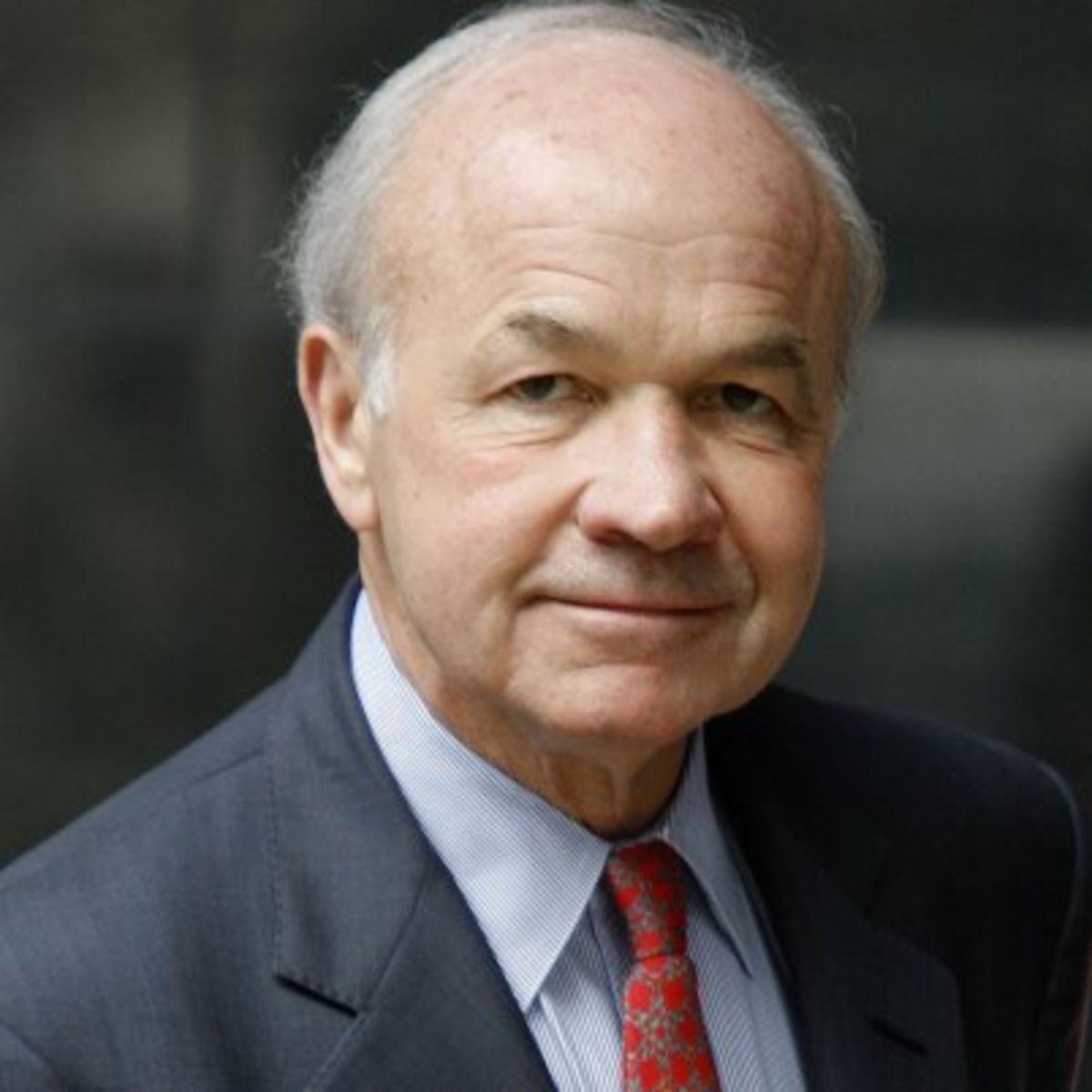

I recognize that he is not the most popular fellow in Houston investment circles these days, but is anyone else but me a tad uncomfotable that the federal government is running roughshod over R. Allen Stanford?

I recognize that he is not the most popular fellow in Houston investment circles these days, but is anyone else but me a tad uncomfotable that the federal government is running roughshod over R. Allen Stanford?

As everyone following the Stanford Financial Group scandal knows by now, at the request of the Department of Justice, U.S. District Judge David Hittner overruled a federal magistrate’s order last week that would have allowed Stanford to remain free on bond pending his trial on business fraud charges. As a result, Stanford is imprisoned in Houston’s Federal Detention Center pending his trial, which will probably not occur until sometime next year.

Meanwhile, the DOJ, the SEC, a federal court-appointed receiver and a British receiver operating in Antigua have frozen all of Stanford’s personal assets, as well as the assets of the Stanford Financial empire. Consequently, Stanford has no funds with which to retain counsel.

And now he doesn’t even have the freedom to help his attorneys prepare his defense.

However, it’s now become reasonably clear that the DOJ and the SEC’s repeated public allegations that Stanford was running a Ponzi Scheme through Stanford Financial are, if not outright false, at least misleading and irresponsible.

Stanford Financial clearly owned substantial assets, including the Antiguan Bank that also owned substantial assets itself. Perhaps those assets were over-valued and perhaps Stanford and his associates misled investors on the bank’s capability of repaying the certificates of deposit that the company promoted and sold. But that’s a far cry from running a Ponzi Scheme.

Moreover, the government’s efforts to prevent Stanford from paying for defense counsel are downright scary.

The fact that Stanford Financial is not in a position to pay them is not particularly surprising. The company would probably be in bankruptcy if it were not already in receivership, and it’s unlikely that either a bankruptcy judge or a U.S. district judge would allow the company to pay for Stanford’s criminal defense.

But putting aside for the moment the issue of Stanford not being allowed to use his personal assets to defend himself, Stanford Financial has a Director’s & Officer’s insurance policy that provides for payment of at least a portion of Stanford’s defense However, the Stanford Financial receiver has threatened to seek contempt charges against the insurer (Lloyds) if it pays Stanford’s defense costs as it is contractually obligated to do under the policy. At the same time, the receiver, the DOJ, and the receiver are spending millions in preparing the case against Stanford. My conservative estimate is that the government’s tab is more than $25 million already (the receiver alone has a pending request for $20 million in fees).

Finally, Stanford has exhibited absolutely no inclination to flee from the charges against him. He has numerous family ties to Texas and the Houston area, and he has no prior criminal record. And it’s not as if Stanford can just walk away from the charges if he is allowed out on bond. He has no passport and, with the GPS tracking device that the U.S. Marshal’s Office requires criminal defendants to wear these days, the U.S. Marshals know immediately when a defendant is going somewhere that he is not supposed to be.

It’s easy to look the other way when this type of concerted effort by the federal government essentially strips an unpopular businessman of the capacity to defend himself against charges that could imprison him for the rest of his life.

But remember — if it can happen to R. Allen Stanford, then it can certainly happen to you and me.

A copy of Stanford’s motions seeking release of funds for his defense and for reconsideration of his detention order are below.