A frequent topic on this blog has been the unjust nature of the government’s questionable tactic of bludgeoning business executives into plea bargains by playing on the executive’s fear of a draconian prison sentence (often an effective life sentence) if the executive has the temerity to assert his or her Constitutional right to a fair trial by jury.

A frequent topic on this blog has been the unjust nature of the government’s questionable tactic of bludgeoning business executives into plea bargains by playing on the executive’s fear of a draconian prison sentence (often an effective life sentence) if the executive has the temerity to assert his or her Constitutional right to a fair trial by jury.

Although prosecutors justify such tactics as a reasonable tool in seeking the truth about criminal acts of others, plea bargainers often undermine that goal by testifying falsely in order to obtain the favorable terms of the deal.

Moreover, the Enron Task Force’s bludgeoning of plea bargains has been particularly egregious because the Task Force is not using the tactic to promote the truth. Rather, as reflected by the strong evidence of witness tampering in all of the Enron-related criminal cases, the Task Force has been intimidating huge numbers of witnesses (114 in the Lay-Skilling-Causey case alone!) who would testify favorably for the defendants in those cases. That tactic has already resulted in the jury in the Nigerian Barge case not hearing the full story in that case, contributing to the imprisonment of four innocent former Merrill Lynch executives.

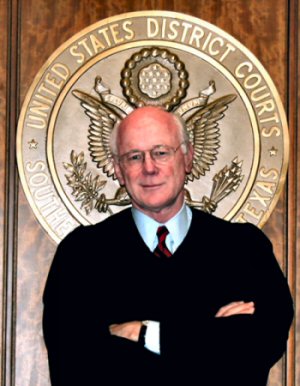

Although one judge is currently grappling with how to deal with the Enron Task Force’s witness tampering tactics, another judge — U.S. District Judge Lynn Hughes — recently made clear during a hearing in another Enron-related criminal case that he is highly skeptical of the Enron Task Force’s bludgeoning of a plea bargain from a former Enron executive who is likely going to be a key witness in the upcoming trial against former Enron executives Ken Lay, Jeff Skilling and Richard Causey. You may recall from this previous post that Judge Hughes is not reluctant to criticize the government when it abuses its overwhelming power against individual citizens.

The particular Enron-related criminal case in which Judge Hughes weighed in is that of Christopher Calger, a former Enron North America executive, whose plea bargain was the subject of this previous post. As noted in that post, the case against Mr. Calger involved a somewhat convoluted 2000 transaction known as Coyote Springs II in which Enron North America sold some energy assets to a third party and arranged a hedge of the third party’s risk that Enron North America would not complete the sale of all of the assets.

Although it’s not at all clear that there is anything even questionable — much less criminal — with that transaction, Mr. Calger elected to enter into a plea bargain with the Enron Task Force rather than risk the financial drain and long prison sentence that could result from defending his innocence at trial.

At any rate, when the Task Force decided to announce Mr. Calger’s plea bargain — which just happened to be on the same day that the jury in the Enron Broadband case began jury deliberations (are you still doubting that the Enron Task Force plays fair?) — the judge assigned to the criminal case against Mr. Calger was out of town and unavailable to take the plea.

Rather than postpone the hearing and lose the opportunity to taint the Enron Broadband jury with publicity about another admission of guilt in connection with an Enron-related case, the Task Force elected to proceed with the hearing on Mr. Calger’s plea bargain in front of Judge Hughes, who has not been assigned to any Enron-related criminal cases.

Although mainstream media accounts of the hearing on Mr. Calger’s plea bargain reported nothing about what actually occurred during the hearing, the transcript of the hearing (download here) reveals that the Task Force’s decision to proceed with the hearing in front of Judge Hughes nearly backfired.

Beginning on page 9 of the 23 page transcript (p. 11 of the pdf), Judge Hughes begins questioning both Mr. Calger and then the Enron Task Force prosecutor regarding the nature of the alleged offense. Very quickly, it becomes clear from the transcript that the Task Force prosecutor neither understood the underlying transaction involved in the indictment of Mr. Calger nor could articulate precisely what crime Mr. Calger had committed.

At the end of the pointed questioning, Judge Hughes gave Mr. Calger an opportunity to reject the plea bargain, which he declined to do. As a result, Judge Hughes accepted the plea bargain, although it is clear from the transcript that he was not comfortable in doing so.

So, what really is the bigger problem to American society and the rule of law — criminal business executives or out-of-control prosecutors?

Picking up on the subject addressed previously

Picking up on the subject addressed previously