Over at Point of Law.com, Moin Yahya, Assistant Professor of Law Faculty of Law at the University of Alberta, is dissecting the prosecution against Conrad Black (earlier posts here) in a series of posts, the first two of which are here and here. Unless you are in favor of the expansion of federal criminal power, his findings are troubling. Take, for example, the obstruction of justice charge against Lord Black:

Over at Point of Law.com, Moin Yahya, Assistant Professor of Law Faculty of Law at the University of Alberta, is dissecting the prosecution against Conrad Black (earlier posts here) in a series of posts, the first two of which are here and here. Unless you are in favor of the expansion of federal criminal power, his findings are troubling. Take, for example, the obstruction of justice charge against Lord Black:

One of the charges that the prosecution added against Black was obstruction of justice. This charge was added at the last minute and was not in the initial indictment. The charge related to the fact that Black removed boxes of documents from the offices of Hollinger Inc. (which was the parent company of Hollinger International the American company based in Chicago). The order not to remove the boxes had been issued by a Canadian judge in Toronto. (As an aside, wouldnít a simple contempt of court charge have sufficed?)

What jurisdiction did the United States have over Black for an event that took place on foreign soil? Putting aside the question of whether the prosecution already had these documents, so it is not clear that his removal obstructed any investigation; the more important and troubling aspect of this case is the creeping federalization of American law not just inside the United States but abroad. [. . .]

But now, will Congress seek to regulate the conduct of Americans and American corporations all over the world? . . . [A]s we have seen before, the courts cannot seem to find that magic bright line to constrain Congress . . . Today Congress regulates sex tourism, truly a noble cause, but tomorrow what else will it decide on. Will it outlaw dog-fighting in foreign lands? Will Congress criminalize paying workers in developing countries less than the minimum wage in the United States? Will Congress criminalize not following the mandates of Sarbanes-Oxley even if the American company is only listed on a foreign exchange? What then will be the result? The answer depends on your view of whether federalism is good or bad. If the growth of Congressional power concerns you, then these latest cases should cause you more concern; if not, then not.

Update: Professor Yahya’s third segment is here.

By the way, it sounds as if Houston business executive and philanthropist Dan Duncan is getting a dose of what Professor Yahya is talking about:

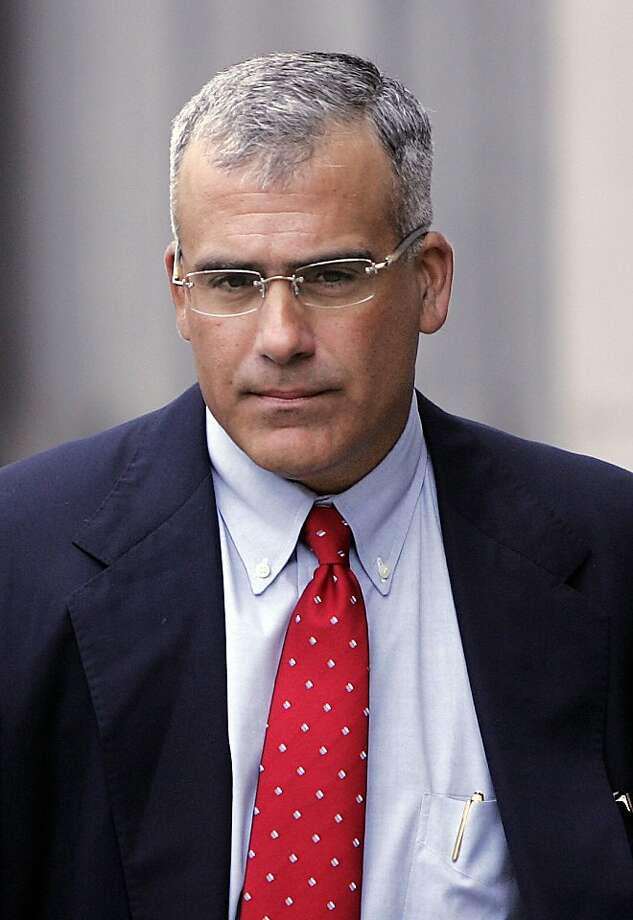

A 2002 big game hunting trip in Siberia could bring big trouble for Houston billionaire Dan Duncan.

The 74-year-old founder of pipeline giant Enterprise Products Partners may face criminal charges following his appearance Wednesday before a grand jury in Houston, where he answered questions about the trip he and other hunters took with Russian guides.

During the trip, Duncan shot and killed a moose and a sheep while riding in a helicopter, a practice Duncan said he did not know was illegal in Russia. Neither animal was considered endangered, he said.

Russian officials were aware of the hunting expedition ó Duncan’s attorney Rusty Hardin said the guide on the trip is now a top official with the Russian Federation’s hunting licensing agency ó but there were no complaints or charges filed in that country.

Hardin said prosecutors from Washington, D.C., may use the Lacey Act, a 107-year-old law designed to prevent the interstate and international trafficking of rare plants and animals, to bring felony criminal charges against Duncan. If found guilty he could face jail time, Hardin said.

“What the hell is the U.S. interest in bringing felony charges here for hunting on Russian soil, where not one single person has complained?” Hardin said Wednesday. “Is this really the best use of our prosecutorial resources?”

Read the entire article.

When Michael Dell jumped back into hot CEO seat at Austin-based Dell Inc in February, I wondered whether he and the company would benefit from application of what Larry Ribstein has brilliantly coined “

When Michael Dell jumped back into hot CEO seat at Austin-based Dell Inc in February, I wondered whether he and the company would benefit from application of what Larry Ribstein has brilliantly coined “ With the Conrad Black trial

With the Conrad Black trial