The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman — who does a fine job of reporting on matters relating to Houston’s Texas Medical Center — reports today that Dan Duncan, chairman of Houston-based Enterprise Products Partners, LP, has donated $100 million to Baylor College of Medicine to trigger funding of Baylor’s effort to become the second comprehensive cancer center in Houston’s Texas Medical Center (the other is the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center). The gift follows Duncan’s earlier $35 million gift to Baylor last year.

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman — who does a fine job of reporting on matters relating to Houston’s Texas Medical Center — reports today that Dan Duncan, chairman of Houston-based Enterprise Products Partners, LP, has donated $100 million to Baylor College of Medicine to trigger funding of Baylor’s effort to become the second comprehensive cancer center in Houston’s Texas Medical Center (the other is the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center). The gift follows Duncan’s earlier $35 million gift to Baylor last year.

This is a major development for the Medical Center, which — through M.D. Anderson — is already one of the primary cancer care and research venues in the United States. The collaborative effort of M.D. Anderson and Baylor’s new facility may propel the Texas Medical Center to the forefront of cancer research and care in the entire world.

Category Archives: News – Med Center

M.D. Anderson research center continues to grow

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman reports that the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center has received a $20 million donation from Lowry and Peggy Mays as the cancer center continues raising funds for its 116 acre research park under development about a mile and a half south from the main M.D. Anderson hospital complex in Houston’s Texas Medical Center. The Mays gift to M.D. Anderson comes on the heels of an earlier $30 million gift from the Red McCombs family. Mr. Mays built San Antonio-based Clear Channel Communications into the largest radio station company in the U.S.

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman reports that the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center has received a $20 million donation from Lowry and Peggy Mays as the cancer center continues raising funds for its 116 acre research park under development about a mile and a half south from the main M.D. Anderson hospital complex in Houston’s Texas Medical Center. The Mays gift to M.D. Anderson comes on the heels of an earlier $30 million gift from the Red McCombs family. Mr. Mays built San Antonio-based Clear Channel Communications into the largest radio station company in the U.S.

A great Houstonian

Samuel Ward Casscells, III is a 53 year old M.D. and professor of biotechnology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston in Houston’s amazing Texas Medical Center. He is also an Army medical corps reservist, and recently was awarded both the General Maxwell Thurman Award and the Army Meritorious Service Medal for his service during Operation Iraqi Freedom. In this Houston Chronicle op-ed, Dr. Casscells writes about the reason that he joined the military and the surprising experience that followed:

Samuel Ward Casscells, III is a 53 year old M.D. and professor of biotechnology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston in Houston’s amazing Texas Medical Center. He is also an Army medical corps reservist, and recently was awarded both the General Maxwell Thurman Award and the Army Meritorious Service Medal for his service during Operation Iraqi Freedom. In this Houston Chronicle op-ed, Dr. Casscells writes about the reason that he joined the military and the surprising experience that followed:

I had joined the Army Reserve for what seemed good reasons at the time: to help a hard-working medical corps, to live up to the examples of some of my heroes (Drs. Denton Cooley, James “Red” Duke, Michael DeBakey, and my father, surgical giants who wore Army green), and to set an example for my children.

It proved to be more than that: gripping, inspiring and filled with surprises. As only one in 200 Americans is in uniform today, most do not know any soldiers; hence this report.

One month after being commissioned, I received a phone call from Army Surgeon General Kevin Kiley: “Col. Casscells, welcome aboard. I want to be ready in case of a flu pandemic. You have some experience. We may even have some fun. Stand by for orders.”

In a few months, I felt like a member of a big family. I would not say a team because there was so little rah-rah, and ó to my surprise ó no bragging, no macho, no arguing and very little politics. Even in the sand, with all the surgeons from Operation Iraqi Freedom, the focus was the mission: how to prevent and treat injuries and illness.

All suggestions were welcome. All are addressed by rank, but the general speaks as respectfully to the sergeant as to a colonel. And there is lots of laughing and gentle teasing (a perennial: the Air Force, always ready, will go anywhere ó as long as there is a dry golf course, and cocktails).

[snip]

Equally wondrous to me: There was not a shred of racial awareness, much less tension. I finally had to ask. The answer is that, since President Truman integrated the Army Officer Corps in 1948, there have been several generations of advancement based on merit (which means hard work, smart work, but especially teamwork). Thus there are thousands of black officers who command with quiet confidence.

Read the entire piece. Hat tip to Clear Thinkers reader Byron Hood for the link to Dr. Casscells’ inspiring op-ed.

Texas Medical Center players make nice

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman, who has done a fine job over the past couple of years of covering the divisive split between former Texas Medical Center partners, Baylor College of Medicine and the Methodist Hospital — reports today that Baylor and Methodist have entered into a settlement brokered by Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott and that Baylor and its new teaching hospital — St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital — have decided to shelve their ongoing merger negotiations for the time being.

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman, who has done a fine job over the past couple of years of covering the divisive split between former Texas Medical Center partners, Baylor College of Medicine and the Methodist Hospital — reports today that Baylor and Methodist have entered into a settlement brokered by Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott and that Baylor and its new teaching hospital — St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital — have decided to shelve their ongoing merger negotiations for the time being.

Whew! Never a dull moment in the Medical Center, eh?

AG intervenes in Baylor-Methodist squabble

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman continues his fine reporting on the saga of the Medical Center divorce between The Methodist Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine with this report that Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott has engaged the feuding ex-partners in a series of meetings over the past two weeks for the purpose of ending the bickering between the institutions, which has been going on for the better part of two years now.

The Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman continues his fine reporting on the saga of the Medical Center divorce between The Methodist Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine with this report that Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott has engaged the feuding ex-partners in a series of meetings over the past two weeks for the purpose of ending the bickering between the institutions, which has been going on for the better part of two years now.

In the meantime, Mr. Ackerman reports that, even as the talks took place, eleven Baylor cardiologists left for Methodist, bringing to 80 the total number of physician and faculty defections that Baylor has suffered since the split in April, 2004. Previously, Baylor departments of pathology, neurology/neurosurgery, plastic surgery, anesthesiology and orthopedics suffered physician or faculty losses to Methodist.

A former Houstonian, Mr. Abbott clearly is taking a special interest in resolving the Baylor-Methodist feud that has shaken Houston’s Texas Medical Center. Mr. Abbott was a young attorney in private practice in Houston during the early 1980’s when he was paralyzed from the waist down after being seriously injured by a falling tree branch while jogging at Houston’s Memorial Park. Mr. Abbott was treated at Medical Center hospitals, and he has often publicly expressed his appreciation for the extraordinary treatment that he received there, particularly his rehabilitation stint at The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research (known as “TIRR”). As such, he is a powerful voice for the public interest in mediating the Baylor-Methodist dispute.

The politics of charity in the world of health care

Wealthy Houston plaintiff’s lawyer John O’Quinn (earlier posts here and here) recently proposed to donate $25 million to St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital — the largest gift in the hospital’s 50 year history — in return for renaming the hospital’s highly-recognizable medical tower the “O’Quinn Medical Tower at St. Luke’s.”

Wealthy Houston plaintiff’s lawyer John O’Quinn (earlier posts here and here) recently proposed to donate $25 million to St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital — the largest gift in the hospital’s 50 year history — in return for renaming the hospital’s highly-recognizable medical tower the “O’Quinn Medical Tower at St. Luke’s.”

Well, the Chronicle’s Todd Ackerman, who does a fine job of staying on top of Medical Center stories, reports in this article that the St. Luke’s board’s decision to accept the donation from Mr. O’Quinn is not going over well with a number of St. Luke’s doctors:

The plan to rename the edifice after John O’Quinn in recognition of a $25 million donation by his foundation has infuriated many St. Luke’s doctors, who last week began circulating a petition against it and Monday night convened an emergency meeting of the medical executive committee.

The Robertsons of Houston

The late Corbin Robertson, Sr. was a bright business mind when he came to Texas as a young man from Minnesota in the 1940’s. After marrying Wilhelmina Cullen — the daughter of famous Houston wildcatter Hugh Roy Cullen — Mr. Robertson ultimately became the brains behind the investment of the Cullen Family oil and gas fortune, a role that Richard Rainwater successfully emulated decades later for Ft. Worth’s Bass Family. Houston benefitted greatly from Mr. Robertson’s business acumen as both the Cullen and Robertson families became among Houston’s greatest philanthropists, contributing huge amounts to institutions such as the University of Houston and the Texas Medical Center.

The late Corbin Robertson, Sr. was a bright business mind when he came to Texas as a young man from Minnesota in the 1940’s. After marrying Wilhelmina Cullen — the daughter of famous Houston wildcatter Hugh Roy Cullen — Mr. Robertson ultimately became the brains behind the investment of the Cullen Family oil and gas fortune, a role that Richard Rainwater successfully emulated decades later for Ft. Worth’s Bass Family. Houston benefitted greatly from Mr. Robertson’s business acumen as both the Cullen and Robertson families became among Houston’s greatest philanthropists, contributing huge amounts to institutions such as the University of Houston and the Texas Medical Center.

Medical Center institutions rank highly again

U.S. News & World Report’s annual “America’s Best Hospitals” survey is out again and, as usual, Houston’s Texas Medical Center is well-represented in the lists of the top hospitals in a number of different categories. Here is a previous post on the 2004 survey.

U.S. News & World Report’s annual “America’s Best Hospitals” survey is out again and, as usual, Houston’s Texas Medical Center is well-represented in the lists of the top hospitals in a number of different categories. Here is a previous post on the 2004 survey.

The U.S. News and World Report survey ranks the country’s top 50 hospitals in 17 specialties. Less than a third of the 6,000 U.S. hospitals meet the eligibility criteria and only 176 of those institutions qualified for a ranking. The rankings are based on a survey of board-certified physicians around the country, patient survival data and various other indicators, such as the ratio of nurses to patients, technologies and services available to patients, the number of discharges over a three-year period, and whether the institution has Magnet status as determined by the American Nurses Credentialing Center.

M.D. Anderson was again ranked as one of the top two hospitals in cancer care, a position that it has held since U.S. News and World Report began its annual survey in 1990. M.D. Anderson held the No. 1 position in 1992, 2000, and 2002 through 2004. M.D. Anderson also ranked fifth in gynecology, and 11th in both otolaryngology (i.e., ear, nose and throat diseases) and in urology.

Other Medical Center institutions also ranked highly in various categories. Texas Children’s Hospital ranked fourth in pediatrics, while The Menninger Clinic ranked tenth in psychiatry and The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research (known as “TIRR”) ranked fifth in rehabilitation. The Texas Heart Institute at St. Luke’s Hospital ranked eighth in heart and heart surgery, while St. Luke‘s also ranked 40th in urology and 42nd in kidney disease. Memorial Hermann Hospital — the teaching hospital for the University of Texas Health Science Center — was ranked 41st in kidney disease and 49th in urology.

Finally, the The Methodist Hospital ranked in more specialties than any other Texas hospital — tenth in neurology and neurosurgery, 13th in urology, 14th in opthamology, 16th in heart and heart surgery, 17th otolaryngology, 19th in psychiatry and 42nd in gynecology.

As I have noted many times, not only is the Texas Medical Center one of Houston’s largest centers of employment, it is an amazing collection of medical services talent.

McCombs makes huge gift for M.D. Anderson research

San Antonio-based businessman Red McCombs has given the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center $30 million for its huge $500 million research park that will eventually consist of six centers focusing on cutting edge areas of cancer research.

San Antonio-based businessman Red McCombs has given the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center $30 million for its huge $500 million research park that will eventually consist of six centers focusing on cutting edge areas of cancer research.

The gift — which is one of the two largest that M.D. Anderson has ever received — will go to help fund the developing Red and Charline McCombs Institute for the Early Detection and Treatment of Cancer on M.D. Anderson’s 116-acre south campus. That campus is about a mile and a half from the main M.D. Anderson hospital complex in the Texas Medical Center.

Remembering a Special Father

Inasmuch as I am one of ten children of the marriage of Walter M. and Margaret Kirkendall, I have a large number of family members (over 30 nieces and nephews at last count), many of whom are regular readers of this blog.

Inasmuch as I am one of ten children of the marriage of Walter M. and Margaret Kirkendall, I have a large number of family members (over 30 nieces and nephews at last count), many of whom are regular readers of this blog.

This particular blog post is primarily for those family members and our family friends, but even if you are not a member of those groups, feel free to read on and learn about a special father and a remarkable Houstonian.

The memory of where I was when my father died remains indelibly etched on my mind.

Shortly after 8:00 a.m. on Saturday morning, July 13, 1991, I was preparing to play golf in Iowa City, Iowa at Finkbine Golf Course during my 20th high school reunion. Unexpectedly, the pro shop summoned me from the first tee that I had a telephone call. When I reached the phone, my brother Matt was on the line with terrible news.

Our father, Walter M. Kirkendall had suffered a serious heart attack moments earlier in a Chicago-area hotel room while preparing to attend our cousin and his niece Sarah’s wedding with our mother.

At the time of the call, Matt did not know whether our father had survived the attack. Minutes later, after I had quickly returned to my hotel room to gather my things for a hurried trip to Chicago, Matt called again. Our father had died that morning in Chicago at the age of 74, probably before I had left the golf course in Iowa City.

Consequently, my memories of Walter Kirkendall’s death are inextricably intertwined with golf. To a large degree, that is utterly appropriate because, over the final 15 years of his life, Walter and I spent countless hours together golfing.

These regular golf games began in 1976 when I entered law school at the University of Houston. Back then, we would rise early most weekend and holiday mornings to play the back nine at the venerable Memorial Park Golf Course in Houston.

In 1982, we transferred those weekly games at Memorial to several Houston-area clubs, concluding at Lochinvar Golf Club. The final time I saw Walter alive was the Sunday morning before his death when we played golf together at Lochinvar. Inasmuch as he played quite well that day, one of my enduring memories of Walter is his chortling in the clubhouse as he collected his golf bets from me.

Thus, my golfing memories of Walter are surrounded by an aura of good fortune and warm appreciation. Good fortune because golf allowed me to enjoy many hours of Walter’s wisdom, insight, and humor. Warm appreciation because golf allowed me to give something back to this man who premised his life on giving to others.

You see, despite his love of golf, Walter never became an active member of a private golf club. Walter gladly sacrificed something that would have been primarily for his enjoyment — that is, golf on a private course — for what he considered the more important needs of his large (ten children!) family.

Accordingly, as I joined several golf clubs over the final decade of Walter’s life, I made a point to give Walter an opportunity to play golf at those clubs as much as he wanted. His pure enjoyment of our golf outings is one of my life’s greatest satisfactions.

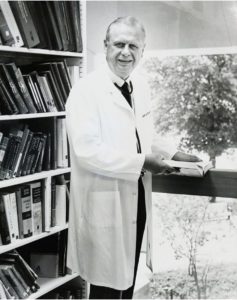

In addition to being a special father, Walter Kirkendall was a remarkable doctor and teacher.

Born in 1917 and raised in Louisville, Kentucky, Walter graduated from the University of Louisville Medical School in 1941 and then went to the University of Iowa in Iowa City for an internship the following year.

As with many men of his generation, Walter finished his internship and residency at Iowa just in time to serve three years as an Army medical officer in North Africa and Italy during World War II, after which he returned to Iowa City to complete his training in medicine.

In 1949, Walter joined the University of Iowa Medical School Faculty and — along with esteemed colleagues such as Jack Eckstein, William Bean, Lew January, Frank Abboud and many others — proceeded to play a major role in the development of the University of Iowa’s fine medical school over the next 23 years.

Walter and his colleagues were at the forefront of the post-WWII doctors who embraced the optimistic view of therapeutic intervention in the practice of medicine, which was a fundamental change from the sense of therapeutic powerlessness that pre-WWII medical professors widely taught to medical students.

Several of Walter’s colleagues have told me that Walter’s attitude of therapeutic optimism was his greatest contribution to the education of his students.

Over his 40+ year academic career, Walter developed a program of teaching and research in hypertension and renal disease for which he received national and international recognition.

His first professional publications were on renal disease, but by the mid-1950’s, he was publishing papers on hypertension and the effects of drugs in patients. After 1960, almost all of his 85 abstracts and 72 papers involved research on the clinical pharmacology of hypertension.

In addition to his teaching, research, and service on multiple professional committees, Walter also directed the Cardiovascular Research Laboratories at the University of Iowa from 1958-70 and the Renal-Hypertension Division from 1970-72. Iowa honored Walter for his contributions to the University by awarding him the Distinguished Achievement Award in 1986.

Perhaps most remarkably, however, is that Walter in 1972 — at the age of 55 when most other academics are settling into comfortable surroundings while preparing to retire — decided to uproot his large family and move to Houston where he became the first Chairman of the Department of Medicine at the then-new University of Texas Medical School in Houston’s famed Texas Medical Center.

In Houston, Walter continued his professional passions — teaching, research and clinical medicine — for the remainder of his life at UT-Houston. In addition to being the first Chairman of the Department of Medicine, Walter was director of UT-Houston’s Hypertension Unit from 1976 and director of the General Medicine Division from 1982 until his death.

During his 20 years at UT-Houston, Walter became the patriarch of UT-Houston’s faculty and student body, reflected by the UT-Houston alumni awarding him the first Benjy F. Brooks Medal in 1991 as the outstanding clinical faculty member, the school’s naming of it’s internal medicine library and suite in Walter’s honor, and the Walter M. Kirkendall Endowed Lecture Series that UT-Houston sponsors each year.

So, the foregoing outlines Walter’s remarkable professional legacy — two institutions served for over 20 years each while teaching and pursuing cutting edge research in a key area of medicine throughout his career. The late James T. Willerson, M.D., former president and medical director of the Texas Heart Institute, observed the following in his eulogy at UT-Houston’s memorial service for Walter:

Dr. Frank Abboud called me two days ago, wanted to come join me yesterday, early in the morning to visit and talk about Dr. Kirkendall, and then go to his funeral with me. . . Dr. Abboud told me that people in Iowa at the Medical School had never felt that Dr. Kirkendall had left. He was still there.

What he had given, what he represented, what he continued to give was part of Iowa. Can you imagine having that impact on an institution, and people years after you’ve left? Dr. Kirkendall did. How many of us could claim the same thing, ever?

But the foregoing doesn’t adequately convey Walter’s truly endearing qualities. He was a devoted teacher to his medical students and residents, and was constantly interested in the development of their careers. Patients appreciated his thoroughness, fairness and profound concern for them and their families. Many conversations with Walter invariably turned to stories about his aversion to wastefulness, the clutter in his office, his sense of humor, his competitiveness, and his suspicion that the sodium ion is bad for one’s health.

The following eulogies that were given at Walter’s funeral and memorial service elaborate on these qualities: the eulogy of my brother Bud, who is a district judge in Seguin, TX; my eulogy; the eulogy of my brother Matt, who is an internist in Dubuque, Iowa; the memorial service closing of my sister Mary, who is a pediatric emergency room physician in San Antonio; the eulogy of Dr. Willerson; the eulogy of the late Dr. Chevis M. Smythe, and the eulogy of Dr. Philip Johnson.

I close with two of my favorite stories about Walter. One is recounted by Tom S. McHorse, M.D., former president of the Travis County, Texas (Austin) Medical Association. Dr. McHorse recalls vividly his experience with Walter in examining a patient while in medical school:

The setting is the University of Iowa Hospital staff service ward one February morning.

For physicians who graduated after 1980, ward is defined as a large room with eight to ten patient beds separated by curtains, as many emergency rooms currently have.

As medicine was practiced in 1968, acute MIs, bacterial endocarditis, and other illnesses were treated in hospital for six weeks or more. The patient in bed four was such an extended stay patient.Dr. Kirkendall was rounding with his entourage of residents and nurses.

As we approached this frequently examined patient, a distinct change was obvious from the day before. The patient truly had the worst “soup bowl” haircut you can imagine. At bedside, Dr. Kirkendall addressed his first question to the patient:

“Who cut your hair?”

“The hospital barber,” replied the patient, somewhat taken aback.

Dr. Kirkendall was clearly not pleased as he turned to his residents and declared:

“Incompetence at any level should not be tolerated.”

I have no memory of the patient’s diagnosis or anything else Dr. Kirkendall taught us that week, but I have long remembered that statement of Dr. Kirkendall.

The second story was passed along by Dr. Smythe in his eulogy during UT-Houston’s memorial service for Walter, in which he recounted a particularly personal experience with Walter:

Now, at this time, I want to skip ahead to something very personal.

1975-76 was also not a bed of roses at this institution. And, when I was bounced out of the Dean’s Office, I was profoundly hurt, very profoundly hurt, and, I was also puzzled. Since those who were relatively active in my demise had been the people to whom I was closest, I was also alone and considerably puzzled as to whom to turn.

Now, Dr. Kirkendall himself was under no mean pressure at that same time. And indeed, the forces that were playing on us were pretty much identical.

But Walter is the person who said “Cheves, come to my office every Thursday at 11:00 o’clock.” And, he was a person who said “I will help you retrain yourself as a physician.”

And, he did. And that episode illustrated this man’s extraordinary generosity of spirit more than anything that I’ve ever seen. I will be grateful to him for the rest of my life.

Walter’s understanding of the importance of service to others is the thread that binds the fabric of families, friendships, schools, professions, communities, and, ultimately, societies.

In his quiet and confident manner, Walter understood the importance of his life’s work, and this understanding formed the cornerstone of his unshakable sense of fulfillment and contentment in his personal and professional life.

In my book, that’s quite a fine legacy, and I am taking this Father’s Day to appreciate my blessing to have been touched by it.