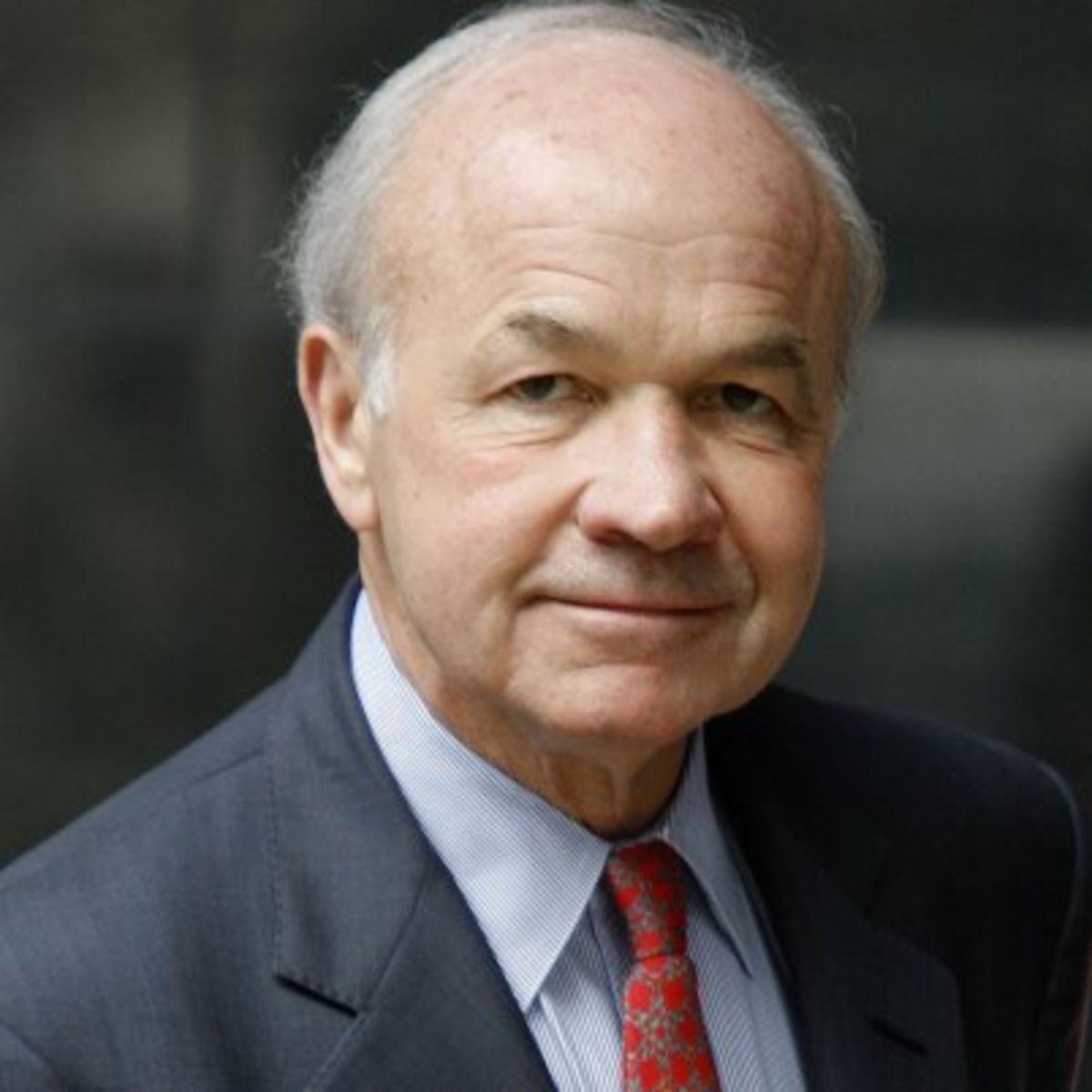

The attorneys for former Enron CEO Jeff Skilling filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court yesterday, which is quite interesting and is being widely reported in the mainstream media.

The attorneys for former Enron CEO Jeff Skilling filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court yesterday, which is quite interesting and is being widely reported in the mainstream media.

However, as interesting as a Supreme Court appeal is, that is not the most interesting aspect of the Skilling case right now.

But first the petition.

As usual, Skilling’s legal team at O’Melveny & Myers did an outstanding job in lucidly presenting why the Supreme Court should consider Skilling’s appeal.

In short, Skilling’s petition contends that the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal’s decision in Skilling’s appeal made a mess of two key issues:

(i) application of the honest services wire fraud statute (18 U.S.C. § 1346) to Skilling’s actions, and

(ii) application of the standard for deciding the proper venue for Skilling’s trial in the face of a presumption of community prejudice against Skilling.

As noted previously, the Fifth Circuit panel’s decision in Skilling’s appeal failed to reconcile its reasoning in upholding Skilling’s conviction for honest services wire-fraud under 18 U.S.C. § 1346 with earlier Fifth Circuit panel decisions on the same issue in the Nigerian Barge and Kevin Howard cases.

Inasmuch as there is now a clear split between Fifth Circuit decisions and other circuit appellate courts on the scope of honest services wire-fraud, the issue appears ripe for Supreme Court consideration. Indeed, Skilling’s petition notes Supreme Court Justice Scalia’s recent observation about the need for the high court to take up the issue:

“Without some coherent limiting principle to define what ‘the intangible right of honest services’ is, whence it derives, and how it is violated, this expansive phrase invites abuse by headline grabbing prosecutors in pursuit of local officials, state legislators, and corporate CEOs who engage in any manner of unappealing or ethically questionable conduct.” Sorich v. U.S., 129 S.Ct. 1308, 1310 (2009). [. . .]

There is a “serious argument” that, as Justice Scalia put it, “a freestanding, open-ended duty to provide ‘honest services’—with the details to be worked out case-by-case”—amounts to “nothing more than an invitation for federal courts to develop a common-law crime of unethical conduct.” Sorich, 129 S.Ct. at 1310. And because the notion that courts can “discover[]” whether conduct is criminal using common-law reasoning is “utterly anathema,” [cite deleted] there is an equally serious argument that § 1346 is unconstitutionally vague. [cite deleted].It should not be the task of federal courts to save a facially vague and unenforceable statute from itself. Only Congress can properly demarcate the boundaries of honest-services fraud. . .

Yeah, we know all about those “headline grabbing prosecutors,” don’t we?

The venue issue is even simpler. Skilling argues that the Fifth Circuit improperly allowed U.S. District Judge Sim Lake to rebut a presumption of community prejudice against Skilling through a superficial examination of individual jurors even though the Fifth Circuit concluded that Judge Lake had improperly failed to apply the presumption of community prejudice against Skilling. The Fifth Circuit’s ruling is at odds with several other circuit courts decisions that maintain that such a presumption simply cannot be rebutted, so that conflict between the circuits tees up another Supreme Court issue.

Frankly, given the extensive evidence of both pervasive media bias and prospective juror bias against Skilling, if the Supreme Court allows the Fifth Circuit’s decision to stand on the venue issue, then a denial of a motion to change the venue of a trial within the Fifth Circuit will no longer be grounds for an appeal.

But now for the more interesting developments in Skilling’s case.

Flying almost completely under the radar screen is the fact that the Fifth Circuit decision remanded a portion of Skilling’s case for two reasons.

First, the Fifth Circuit ordered Judge Lake to re-sentence Skilling because of an error that was made in applying a sentencing enhancement in assessing Skilling’s 24-year sentence.

Moreover, the Fifth Circuit decision invited Skilling to file a motion for new trial based on issues of prosecutorial misconduct. Specifically, the Fifth Circuit was particularly concerned about the failure of the Enron Task Force to comply with federal rules requiring the disclosure of exculpatory evidence to the defense from the Task Force’s pre-trial interviews with main Skilling accuser, former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow.

Fastow testified at trial that he told Skilling about the Global Galactic agreement, which purportedly documented a series of illegal “side deals” between Fastow and former Enron chief accountant Richard Causey that guaranteed Fastow would not lose money on certain special purpose entities that he was managing. Skilling denied any knowledge of the purported agreement.

After Skilling’s conviction, the Skilling defense team discovered Fastow interview notes that the Enron Task Force had failed to disclose to the Skilling team prior to trial. Among other things, those notes revealed that Fastow had told the Task Force lawyers that he didn’t think he had told Skilling about the Global Galactic agreement. The Fifth Circuit characterized the Task Force’s non-disclosure as “troubling” in inviting Skilling to file a motion for new trial with the District Court.

So, where does the Fifth Circuit’s remand of the Skilling appeal stand in the District Court?

Well, a review of the District Court docket of Skilling’s criminal case reveals that Judge Lake originally scheduled Skilling’s resentencing for July 30th.

However, in a highly unusual move, Skilling and the prosecution filed a joint motion requesting Judge Lake to put off the re-sentencing indefinitely pending the filing of Skilling’s motion for a new trial, the prosecution’s response to that motion, and the Court’s disposition of the motion. Moreover, the parties requested that the deadline for Skilling’s motion be pushed back to July 10th, which Judge Lake approved.

So, what is going on here?

Could it be that Skilling’s team has discovered even more exculpatory evidence that the Task Force failed to disclose to the Skilling defense prior to the trial?

Could it be that the government’s current lawyers — who were not members of the now disbanded Task Force and who have little incentive to cover for their predecessors — are now finding themselves dealing with a serious failure of the Task Force members to comply with rules requiring the disclosure of exculpatory evidence to the defense in Skilling’s case?

Could the Skilling case be turning into something similar to this?

Stay tuned.

Like this:

Like Loading...

As Congress contemplates an historic extension of governmental control in regard to health care finance, a couple of stories relating to the growth of unrestrained exercise of governmental power in another area grabbed my attention.

As Congress contemplates an historic extension of governmental control in regard to health care finance, a couple of stories relating to the growth of unrestrained exercise of governmental power in another area grabbed my attention.