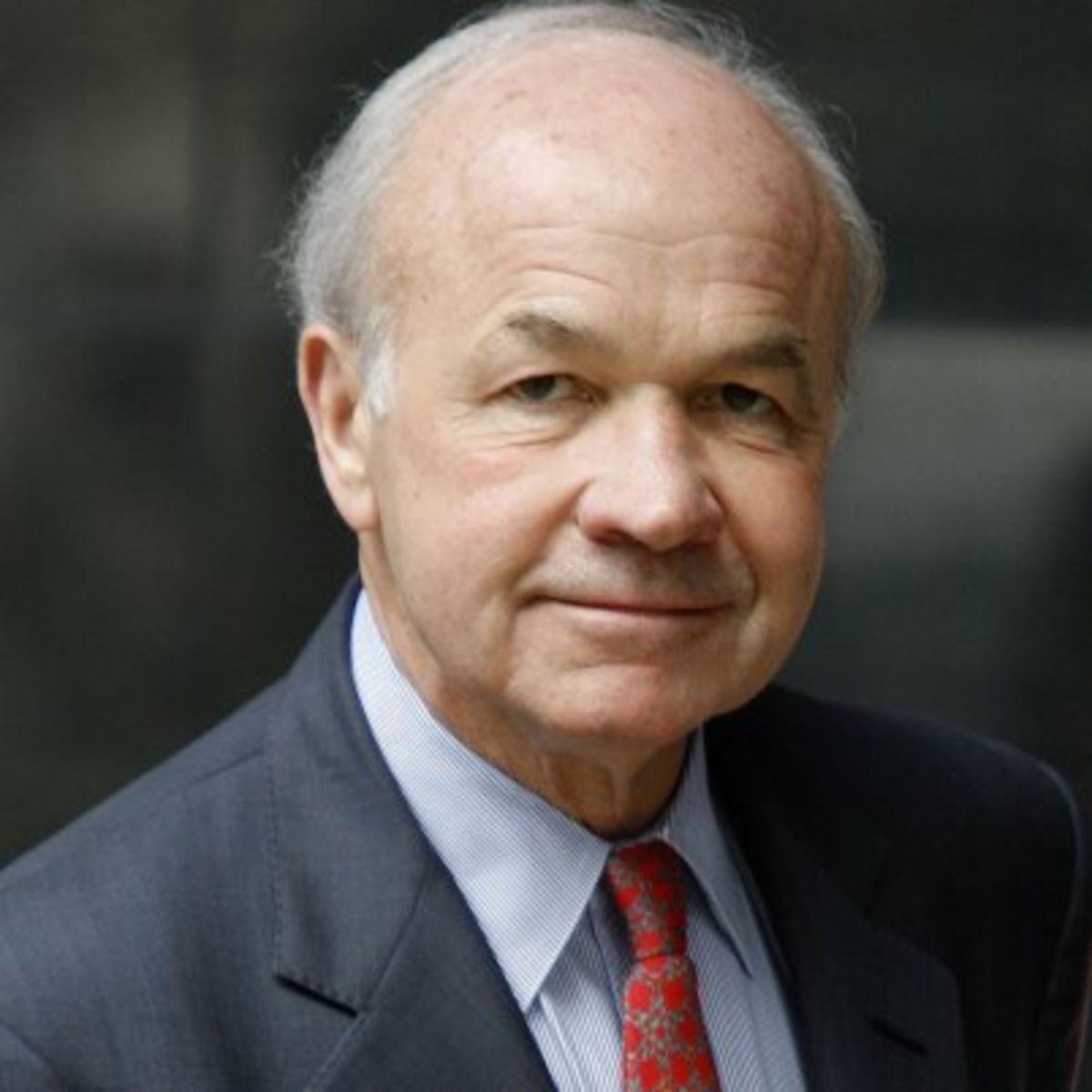

During the criminal trial of Ken Lay and Jeff Skilling, attorney Paul Fisher and economist Jim Johnston of the Heartland Institute authored this piece regarding the unjust prosecution Lay and Skilling that echos a common theme of this blog regarding almost all of the Enron-related criminal prosecutions — that the prosecutions were fundamentally weak criminal cases that were really a smokescreen to promote an underlying political agenda of regulating beneficial risk-taking that generates robust markets, wealth, and jobs.

During the criminal trial of Ken Lay and Jeff Skilling, attorney Paul Fisher and economist Jim Johnston of the Heartland Institute authored this piece regarding the unjust prosecution Lay and Skilling that echos a common theme of this blog regarding almost all of the Enron-related criminal prosecutions — that the prosecutions were fundamentally weak criminal cases that were really a smokescreen to promote an underlying political agenda of regulating beneficial risk-taking that generates robust markets, wealth, and jobs.

Following on their earlier piece, Fisher and Johnston have written this excellent article that speculates on what the business legacy of Lay and Skilling should be. In so doing, Fisher and Johnston note another common theme of this blog — the intrinsic weakness of the convictions against the two executives:

We are left with two convictions that are devoid of any gain to the perpetrators and illogical to the extreme. The real culprit, in our opinion, is the political establishment in California, primarily Democrats, who were intent on punishing a friend of President George W. Bush and his father. While the California Democrats have escaped unscathed, except for ex-governor Davis, the energy trading system is impaired and corporate accounting is now in chaos. It remains to be seen if these institutions will recover any time soon.

However, even more importantly, Fisher and Johnston note the extraordinary wealth creation that resulted from Lay and Skilling’s risk-taking at Enron, and lament how the understanding of the beneficial nature of that risk-taking is now largely lost amidst the media and government-hyped societal condemnation of Lay, Skilling and Enron:

At the end of the day, when the successes and mistakes are tallied for Ken Lay and Jeffrey Skilling, we predict the result on balance will be positive. Perhaps the biggest contribution was to provide risk management of natural gas prices for producers and industrial consumers. Enron operated the over-the-counter market for a year until the exchange-traded futures and options contracts were offered on the New York Mercantile Exchange in 1990. Those futures contracts are now among the most liquid in the world.

The electricity markets established for California are no longer traded. However, there is a market in the PJM (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland) region and an auction is to be established soon in Illinois. In the meantime, natural gas contracts serve as a hedging vehicle because gas is the fuel used at the margin to generate electricity.

Enron’s failed broadband joint venture with Blockbuster was intended to bring video on demand. This now exists on cable and is similar to the iPod offered by Apple Computer. This latter system is a masterful accommodation to copyrighted music and video programming where artists are compensated.

Weather derivatives started by Enron and Koch Industries in 1996 for a swap in the following year have evolved into an exchange-traded contract offered by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Futures and options contracts based on temperatures in 18 U.S., nine European, and two Asia-Pacific cities are now traded in this market.

Finally, the establishment of a robust water market by Enron failed. However, much was learned from the effort and there is optimism about another try.

We fervently hope that Ken Lay and Jeffrey Skilling will be remembered for their extraordinary contributions, rather than their politically-inspired prosecution.

Amen.

As noted in many of my posts on the Lay-Skilling trial and the Nigerian Barge case, the Enron Task Force turned the Enron-related criminal cases into morality plays that appealed to the dynamics of resentment and scapegoating in disingenuously portraying legitimate and productive business transactions as complex frauds.

The result has been a dangerous misuse of the government’s overwhelming prosecutorial power to impose burdensome regulatory costs on valuable markets.

In reality, a far more progressive government policy would be to encourage precisely the type of risk-taking that Lay and Skilling promoted at Enron to facilitate productive markets, employment growth and wealth creation.