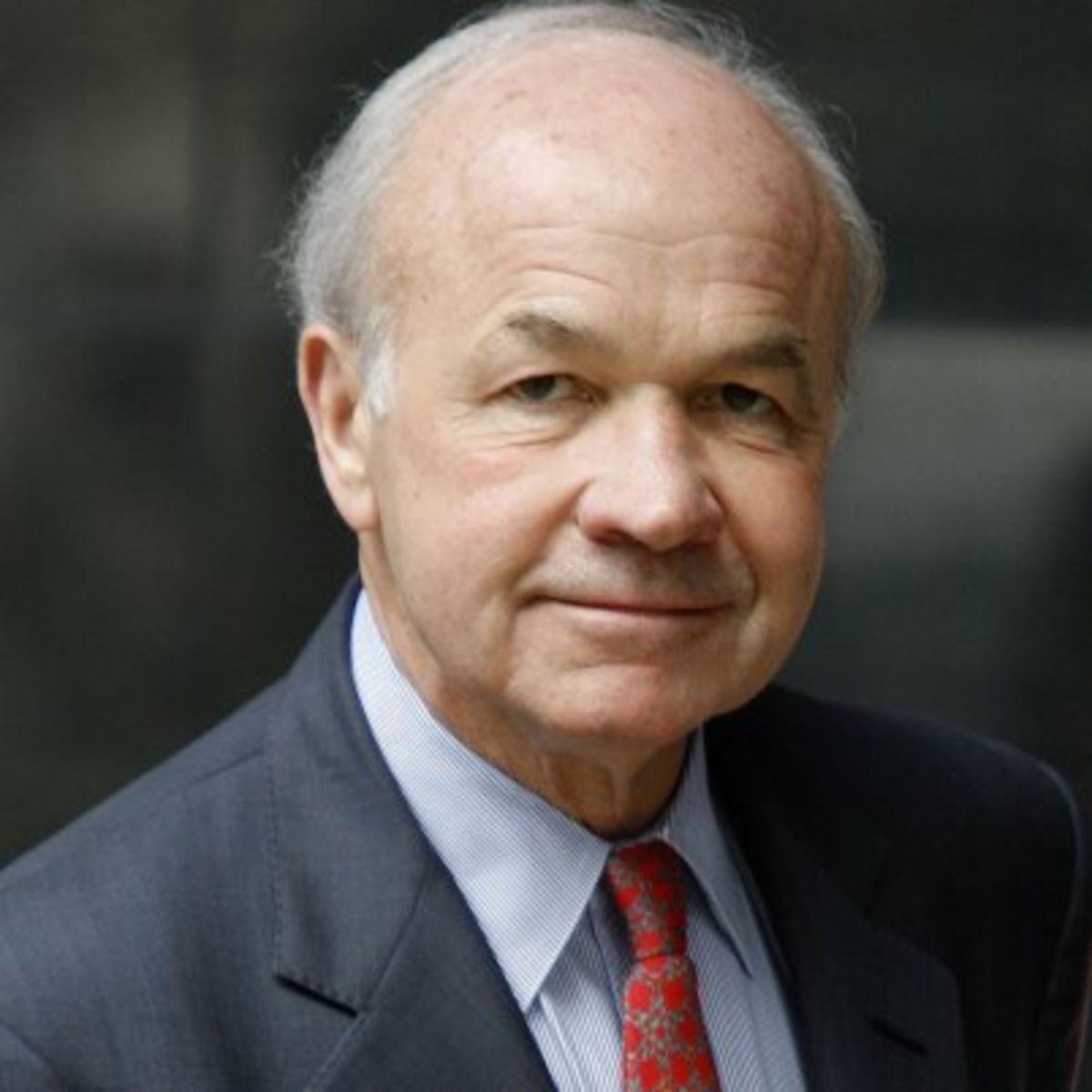

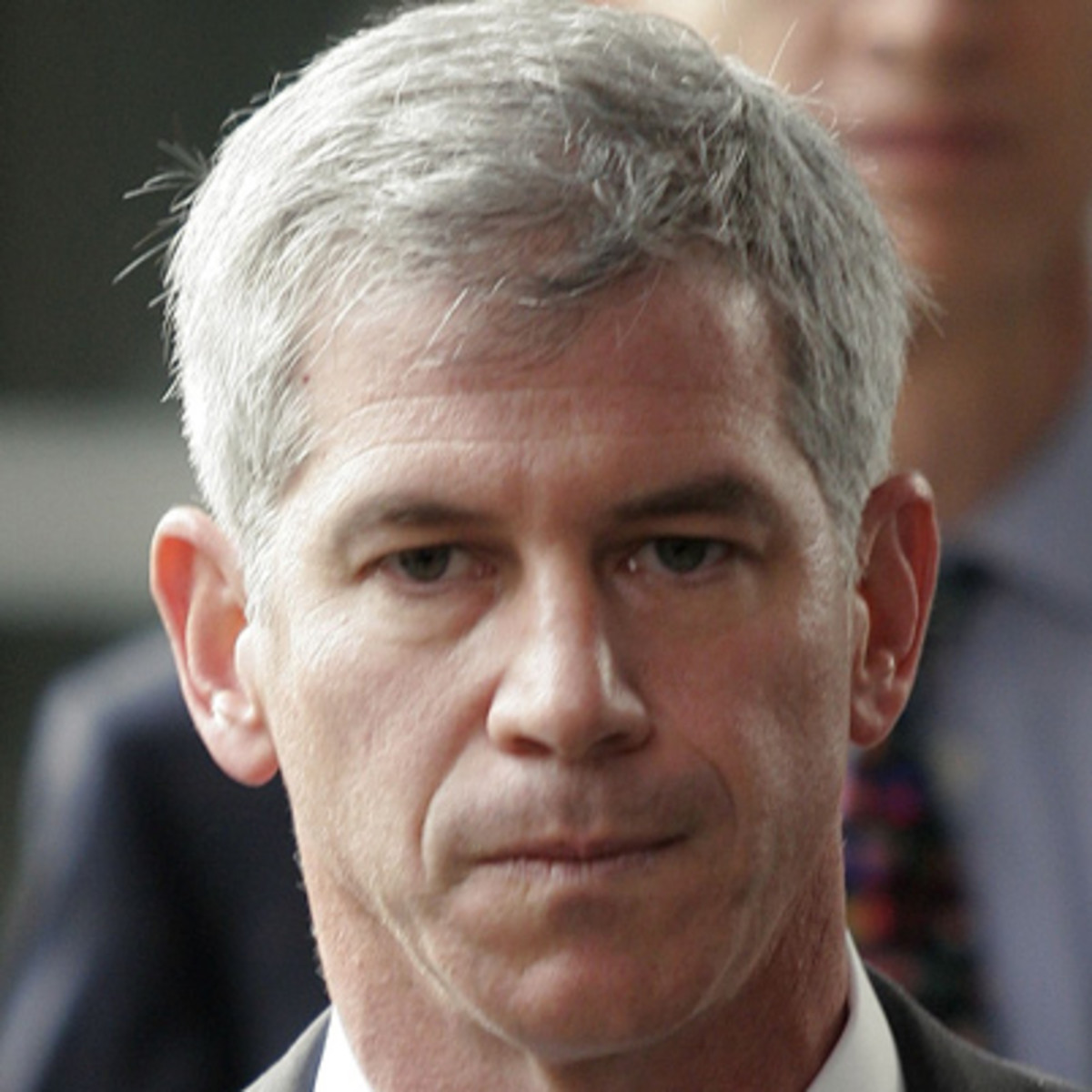

As noted earlier here, the six-year prison sentence handed down earlier last month to former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow was surprising on several levels, not the least of which was that the Enron Task Force elicited testimony from Fastow during the Lay-Skilling trial that his minimum sentence would be ten years.

As noted earlier here, the six-year prison sentence handed down earlier last month to former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow was surprising on several levels, not the least of which was that the Enron Task Force elicited testimony from Fastow during the Lay-Skilling trial that his minimum sentence would be ten years.

The purpose of that testimony was to make Fastow appear to be more credible to the Lay-Skilling jury — he was going to do at least ten years, so he supposedly didn’t have any incentive to lie in order to reduce his sentence.

Thus, it was somewhat surprising that, in the run-up to the Fastow sentencing hearing, Fastow’s attorneys requested a sentence of less than ten years and there was nary a peep from the Task Force objecting to the request.

Then, at the sentencing hearing, the Task Force prosecutors at least tacitly supported the less-than-ten-year sentence by not objecting to Fastow counsel’s requests for leniency to U.S. District Judge Ken Hoyt and even extolling Fastow’s “cooperation” with the Task Force in regard to the Lay-Skilling trial.

Indeed, one of the most surprising aspects of the Fastow sentencing hearing is that neither the Task Force prosecutors nor Fastow attorneys disclosed to Judge Hoyt during the sentencing hearing about Fastow’s contrary testimony during the Lay-Skilling trial.

Or did they? According to this Tom Fowler/Houston Chronicle article, Task Force prosecutors and Fastow’s attorneys met with Judge Hoyt in chambers during a transcribed meeting the afternoon before Fastow’s sentencing.

The transcript of that meeting has not been made public and none of the participants is talking about what was discussed. The Chronicle has filed a motion to unseal the transcript, and neither Fastow nor the Task Force is really opposing the Chronicle’s motion (Fastow has requested that matters regarding his personal medical condition be redacted from the transcript).

But what is really odd about all this is that Fowler reports that the Task Force, in a recent filing that is not yet publicly available, states that it wants to review the transcript of the closed-door meeting because “[t]he government is currently assessing whether to file a notice of appeal of the sentence imposed on Mr. Fastow, and it cannot make that determination without a copy of the transcript of the pre-sentencing hearing.”

Note to Task Force — it’s hard to appeal rulings successfully when you do not object to the ruling in the first place.