Shortly after getting the case, the jury in the criminal trial of former Dynegy and El Paso natural gas traders Michelle Valencia and Greg Singleton (previous posts here) sent U.S. District Judge Nancy Atlas a series of questions that — according to this Kristan Hays/AP article — prompted the judge to observe “they just don’t understand the [the prosecution’s] theories” and may be hung already.

Shortly after getting the case, the jury in the criminal trial of former Dynegy and El Paso natural gas traders Michelle Valencia and Greg Singleton (previous posts here) sent U.S. District Judge Nancy Atlas a series of questions that — according to this Kristan Hays/AP article — prompted the judge to observe “they just don’t understand the [the prosecution’s] theories” and may be hung already.

Yesterday, I noted the defense’s gamble in electing not to put on a case after the prosecution rested based on the bet that the defense could persuade the jury during closing argument that the prosecution had not met its burden of proving that the defendants committed a crime beyond a reasonable doubt. That bet is usually a bad one, but it’s sure looking better in this particular case.

Update: The Chornicle’s John Roper reports that the jury has reached a verdict on wire fraud charges, but has advised Judge Atlas that the jurors are deadlocked on the conspiracy and false reporting charges. Until Judge Atlas decides whether to declare a mistrial or direct the jury to continue deliberating, the nature of the verdict on the wire fraud charges will remain confidential.

Update II: The jury is back and has found Valencia guilty of seven counts of wire fraud and Singleton guilty on a single count of wire fraud. The jury either acquitted or deadlocked on all the other charges against the defendants.

Category Archives: Legal – Criminalizing Business

Key natural gas trader case goes to the jury

In a surprising development, the defense in the trial of former Dynegy trader Michelle Valencia and former El Paso trader Greg Singleton (previous posts here) on conspiracy and fraud charges relating to their submission of false gas trading data to trade publications rested without putting on any evidence, betting that they could persuade the jury during closing arguments that the government had failed to fulfill its burden of proving that Valencia and Singleton are guilty of the charges beyond a reasonable doubt. The Chronicle’s Tom Fowler reports on the closing arguments in the trial here.

In a surprising development, the defense in the trial of former Dynegy trader Michelle Valencia and former El Paso trader Greg Singleton (previous posts here) on conspiracy and fraud charges relating to their submission of false gas trading data to trade publications rested without putting on any evidence, betting that they could persuade the jury during closing arguments that the government had failed to fulfill its burden of proving that Valencia and Singleton are guilty of the charges beyond a reasonable doubt. The Chronicle’s Tom Fowler reports on the closing arguments in the trial here.

The defense strategy is risky, as Jamie Olis discovered when his trial defense team put on a bare bones defense during his trial. The jury in the Valencia and Singleton trial will begin deliberations today.

Finally, Some Justice in the Nigerian Barge Case

As foreshadowed the Fifth Circuit’s decision earlier this month to release from prison three of the four former Merrill Lynch executives pending disposition of their appeal in the Enron-related Nigerian Barge case (extensive discussion here), the Fifth Circuit issued this decision vacating the wire fraud and conspiracy convictions of all four Merrill Lynch executives and reversing the conviction altogether of former mid-level Merrill executive William Fuhs.

As foreshadowed the Fifth Circuit’s decision earlier this month to release from prison three of the four former Merrill Lynch executives pending disposition of their appeal in the Enron-related Nigerian Barge case (extensive discussion here), the Fifth Circuit issued this decision vacating the wire fraud and conspiracy convictions of all four Merrill Lynch executives and reversing the conviction altogether of former mid-level Merrill executive William Fuhs.

Oddly, the Fifth Circuit affirmed the conviction of former Merrill head of Strategic Asset and Lease Finance Group, James Brown on perjury and obstruction of justice charges. That part of the decision will almost certainly be subject to further litigation.

Thus, of the four Merrill defendants, Brown still faces the remainder of his 46 month prison sentence and Fuhs appears to be home free, while former head of Merrill’s Global Investment Banking division — Dan Bayly — and Bayly’s associate — Robert Furst — both face a possible retrial on the charges, although the fact that both have served a year of their sentences before being released from prison last month strongly mitigates against the government prosecuting the case against them again. At least one would think so in a reasonably civil society.

The decision is interesting on several fronts, not the least of which is the division on the panel in deciding the case. Judge E. Grady Jolly wrote the majority opinion of the Court, which was joined by Judge Harold DeMoss with regard to the reversal of Fuhs’ conviction and the vacating of Bayly and Furst’s.

However, Judge DeMoss wrote a spirited dissent in which he persuasively argues that the perjury and obstruction charges against Brown should also be reversed, while Judge Thomas Reavley concurred with the reversal of Fuhs’ conviction and the affirmance of the Brown conviction, but pens a dissent in which he contends the Court should have thrown the book at Bayly and Furst on the mail fraud and conspiracy charges.

The entire decision — particularly Judge DeMoss’ dissent — is entertaining reading, but here are a few excerpts that stand out on first reading. First, the gist of the decision:

We reverse the conspiracy and wire-fraud convictions of each of the Defendants on the legal ground that the government’s theory of fraud relating to the deprivation of honest services – one of three theories of fraud charged in the Indictment – is flawed. We further vacate appellant Fuhs’s conviction on the ground that the evidence is insufficient to support his conviction. Finally, we affirm appellant Brown’s convictions of perjury and obstruction of justice.

Turning to its analysis on the Enron Task Force’s flawed deprivation of honest services theory, the Fifth Circuit falls squarely in line with the Second Circuit’s decision in United States v. Rybicki, 354 F.3d 124, (2d Cir. 2003):

[W]e are guided by the leading opinion on honest-services fraud, the Second Circuit en banc decision in Rybicki, supra. Rybicki concluded, and we agree, that cases upholding convictions arguably falling under the honest services rubric can be generally categorized in terms of either bribery and kickbacks or self-dealing. The great weight of cases are clear examples of such behavior.

Applying Rybicki, the Court observes that the nature of the transaction — even if viewed most negatively toward the defendants — did not involve the type of kickback or bribery that would have tipped off the Merrill executives that the Enron employees were depriving their employer of honest services:

Taking a page from the Supreme Court’s decision in the Arthur Andersen case (which reversed the Fifth Circuit’s decision in that case), the Court noted the following about the expansive interpretation that prosecutors are using in regard to criminal statutes:

This opinion should not be read to suggest that no dishonest, fraudulent, wrongful, or criminal act has occurred. We hold only that the alleged conduct is not a federal crime under the honest services theory of fraud specifically. Given our repeated exhortation against expanding federal criminal jurisdiction beyond specific federal statutes to the defining of common-law crimes, we resist the incremental expansion of a statute that is vague and amorphous on its face and depends for its constitutionality on the clarity divined from a jumble of disparate cases. Instead, we apply the rule of lenity and opt for the narrower, reasonable interpretation that here excludes the Defendants’s conduct.

The Court pulls no punches in criticizing the weakness of the Task Force’s case against Fuhs:

Thus, the Government relies solely on the documentary evidence to assert Fuhs’s knowledge of the oral buyback promise and his intent to participate in the scheme to conceal that promise for the purpose of effecting a misaccounting of the overall deal. We find that the documentary evidence fails to sustain the Government’s burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Much of the Government’s evidence consists of e-mails or memos not written or initiated by Fuhs, not directly addressed to him, and in some cases not even copied to him. They neither recognize a secret oral side deal nor imply that the addressees of the correspondence knew of such a secret deal. While they may support the assertion that Fuhs knew Merrill wanted a buyback agreement to protect its investment, and that it was at one point understood to be part of the deal by Fuhs’ subordinate Geoffrey Wilson, the principal documents relied upon by the Government simply do not sustain the inference that Fuhs had knowledge of an oral guarantee that was to be kept out of the written agreement and kept secret in (because it conflicted with) the accounting of the deal.

And in a wonderful passage that could be used to explain the recent prosecution of the late Enron chairman Ken Lay and former chief executive officer Jeff Skilling as well, the Fifth Circuit observes with regard to the Task Force’s case against Fuhs:

As counsel for Fuhs noted at oral argument, if we begin with the assumption that Fuhs is guilty, the documents can be read to support that assumption. But if we begin with the proper presumption that Fuhs is not guilty until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, we must conclude that the evidence is insufficient to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Fuhs had the knowledge and intent to enter into the fraudulent scheme alleged by the Government.

Before disassembling the perjury and obstruction charges against Brown in his dissent, Judge DeMoss suggests that the deprivation of honest services statute is unconstitutional:

[T]he application of section 1346 to the facts presented in this case is particularly problematic for several reasons, the combination of which poses an even greater harm to future business relationships and transactions than would any one of the problems alone. The Government’s extension of the already ambiguous reach of section 1346 by way of an indictment for conspiracy to commit honest services fraud is especially troublesome. . . . To the extent that . . . case law required a relationship that generated a duty of honest services, such a relationship does not exist in this case between the Defendants, who are employees of Merrill, and Enron or its shareholders, who are the purported victims of the alleged fraud. The limitation of criminal activity to relationships giving rise to a duty of honest services is ignored when any person who negotiates with an employee of another corporation is potentially entangled by the combination of section 1346 with our very broad understanding of conspiracy.

I also believe that a serious problem arises with respect to the Government’s theory of harm in this case. It is absolutely undisputed that Merrill paid $7 million to Enron as a result of the closing of the transaction contemplated by the Engagement Letter of December 29, 1999 that was the final written agreement of the two parties (“the Engagement Letter”). Even granting the Government that Enron paid back $250,000 as the advisory fee to Merrill, Enron still had $6,750,000 more in its bank account as a result of the Engagement Letter than it had before. The Government’s theory of harm would have us ignore the initial gains to Enron and focus solely upon some later loss only tangentially connected to the particular investment transaction that forms the basis of the Indictment.

The cumulative effect of a vague criminal statute, a broad conception of conspiracy, and an unprincipled theory of harm that connects the ultimate demise of Enron to a single transaction is a very real threat, of potentially dramatic proportion, to legitimate and lawful business relationships and the negotiations necessary to the creation of such relationships.

And then Judge DeMoss absolutely nails the utter injustice of Brown’s perjury and obstruction of justice conviction, which is based largely on evidence of terms of the Nigerian Barge transaction that were discussed in negotiations between Enron and Merrill, but never made it into the final contract between the parties:

The conversations preceding the deal are only negotiations, and the ultimate written agreement speaks for itself. Two material facts corroborate this reading: (1) Fastow himself averred to the Government that he, in fact, made only assurances of best efforts to Merrill, not promises or guarantees to take Merrill out of the deal; and (2) in conformance with the written agreement, Merrill actually paid $7 million to Enron, consistent with its purchase of an interest in the barge partnership investment, and therefore had absolutely no legally enforceable claim to be taken out of the deal. The Government mischaracterizes the transaction evidenced by the Engagement Letter when it labels the agreement a “sham” and asserts that Merrill was never “at risk” during the transaction. The Engagement Letter expressly states, “No waiver, amendment, or other modification of this Agreement shall be effective unless in writing and signed by the parties to be bound.” . . . In light of these provisions, Merrill’s $7 million was absolutely at risk. Any oral assurances of a take-out offered to Merrill by any Enron employee would not have been legally binding on Enron. . . .

Merrill could not have enforced Enron’s assurance of its best efforts commitment to remarket the investment interest that Merrill had agreed to purchase; Merrill could only have refused to deal with Enron in the future if the Engagement Letter had resulted in an unsatisfactory business investment. Such negotiations should not be the fodder for criminal indictments. If there is any criminal wrong arising from the facts in this record, and I have serious doubts on that score, it would be in Enron’s employees’ reporting of the transaction described in the Engagement Letter, not in the manner in which Merrill’s employees negotiated the deal.

So, three of the four former Merrill Lynch executives embroiled in the Nigerian Barge case have finally received some reasonable semblance of justice. Although I am happy for these men and their families, let’s not overlook the emotional and financial carnage that has resulted from the Enron Task Force’s dubious decision to criminalize this transaction.

Four successful executives with Merrill Lynch have had their careers badly damaged. The men and their families have had to endure extraordinary stress and pain over the past four years. Lives and careers have been unalterably changed and for what? For having had the misfortune of being involved in a relatively small transaction with the social pariah of the decade, Enron?

Meanwhile, the person most responsible for this damage is doing quite well, thank you.

The prosecution of the Nigerian Barge case was based on resentment and scapegoating, not on justice or any reasonable concept of prosecutorial discretion. This is an increasingly common occurrence in American society and it’s going to take much more than a just reversal in the Nigerian Barge case — or even the deaths of a talented man and an American business institution — to alter this troubling trend of how our government exercises its overwhelming prosecutorial power.

If you don’t believe me, just ask Jim and Nancy Brown.

Update: An insightful reader points out that, with the reversal of the wire fraud and conspiracy conviction, Brown should be in line for a re-sentencing that could reduce his sentence considerably. Inasmuch as U.S. District Judge Ewing Werlein exhibited grace under fire during the original sentencing of the Merrill Four, here’s hoping that Brown’s attorneys can persuade him to reduce Brown’s sentence to time-served (which is well over a year now).

Hope for Sanity in Sentencing of Business Executives?

Although just one case, at least one federal judge has concluded that the resentment and scapegoating that has driven the criminalization of business during the post-Enron era has gone too far.

Although just one case, at least one federal judge has concluded that the resentment and scapegoating that has driven the criminalization of business during the post-Enron era has gone too far.

In this thoughtful sentencing memorandum relating to the conviction of former Impath, Inc. president Richard P. Adelson on conspiracy and fraud charges. U.S. District Judge Jed Rakoff began and concluded his decision — which is ably dissected by Harlan Protass here, Doug Berman here and here and Ellen Podgor here — with the following comments:

This is one of those cases in which calculations under the Sentencing Guidelines lead to a result so patently unreasonable as to require the Court to place greater emphasis on other sentencing factors to derive a sentence that comports with federal law. . .

To put this matter in broad perspective, it is obvious that sentencing is the most sensitive, and difficult, task that any judge is called upon to undertake. Where the Sentencing Guidelines provide reasonable guidance, they are of considerable help to any judge in fashioning a sentence that is fair, just, and reasonable. But where, as here, the calculations under the guidelines have so run amok that they are patently absurd on their face, a Court is forced to place greater reliance on the more general considerations set forth in section 3553(a), as carefully applied to the particular circumstances of the case and of the human being who will bear the consequences. This the Court has endeavored to do, as reflected in the statements of its reasons set forth at the time of the sentencing and now in this Sentence Memorandum prompted by the dictates of Rattoballi. Whether those reasons are reasonable will be for others to judge.

Along the same lines, Ellen Podgor asks all the right questions in regard to the disappointing Second Circuit decision upholding the absurd effective life sentence of former WorldCom CEO, Bernie Ebbers, while Larry Ribstein chimes in with a new SSRN paper, The Perils of Criminalizing Agency Costs. In a related post, Professor Ribstein rams home the essential point:

. . . criminalizing this business practice is not the answer. There is little doubt that the combination of regulation, civil liability and markets can solve — indeed, probably already has solved — any problems here. In fact, criminal charges are so patently not the answer that I suspect that one big effect of this scandal will be a reexamination of the whole issue of criminalizing agency costs.

Meanwhile, Jamie Olis and his family continue their long wait for justice, while three UK bankers bide their time in Houston far away from their families and friends while facing the daunting decision of whether to risk asserting their innocence against the prospect of a long prison sentence if they are convicted within the cauldron of hate that exists in Houston to anyone who had anything to do with Enron.

As Sir Thomas reminds us “do you really think you could stand upright in the winds [of abusive prosecutorial power] that would blow” if that power were to set its sights on you?

What now is the more serious danger to justice and the rule of law? Out-of-control prosecutors and abusive prison sentences for businesspersons? Or the results generated from the risk-taking businesspersons?

The Wylys go to Congress

Following on this previous post from last year, this WSJ ($) article reports that colorful Dallas-based investor Sam Wyly (previous posts here) and his brother Charles get hauled in front of the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations tomorrow in connection with the panel’s investigation into the Wylys’ use of the the Isle of Man tax haven to protect assets and avoid US income taxes.

Following on this previous post from last year, this WSJ ($) article reports that colorful Dallas-based investor Sam Wyly (previous posts here) and his brother Charles get hauled in front of the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations tomorrow in connection with the panel’s investigation into the Wylys’ use of the the Isle of Man tax haven to protect assets and avoid US income taxes.

The Isle of Man is a quasi-independent, largely agrarian republic of about 75,000 people in the sea between England and Ireland that operates under its own financial laws, the most important of which is that a foreign government cannot enforce a claim for unpaid taxes against an Isle of Man entity. As a result, wealthy foreigners for years have used Isle of Man-based shelf corporations and trusts to shield assets and limit taxes. This arrangement has often led to the unusual scene of $1,000 per hour London soliciters and barristers waiting for their court hearing to be called in the Isle of Man courts while the judge (called “the Dempster”) adjudicates a dispute between local farmers over such matters as, say, the ownership of a goat.

The Senate panel has been probing offshore tax havens for several years under the direction of its panel’s senior Democrat, Sen. Carl Levin of Michigan. Interestingly, Sam Wyly is one of the largest benefactors of the business school at Senator Levin’s home state university, the University of Michigan.

As noted in the previous post, the Wylys are already the subject of a criminal investigation by the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, the IRS and the SEC over their Isle of Man arrangements. The WSJ article reveals for the first time that the Wylys were advised on their Isle of Man investments by a network of shady characters, including former attorney David Tedder, a California-based, self-styled “asset-protection expert” who was disbarred in California before moving his practice to Florida in the 1990’s. Tedder is currently serving a five-year federal prison sentence on tax and money laundering charges unrelated to his work for the Wylys.

Unlike most Senate hearings on rather dry financial matters, this one could be pretty entertaining.

The Spokesman for the NatWest Three

What do you do when you can’t hang out and chat with your blokes?

What do you do when you can’t hang out and chat with your blokes?

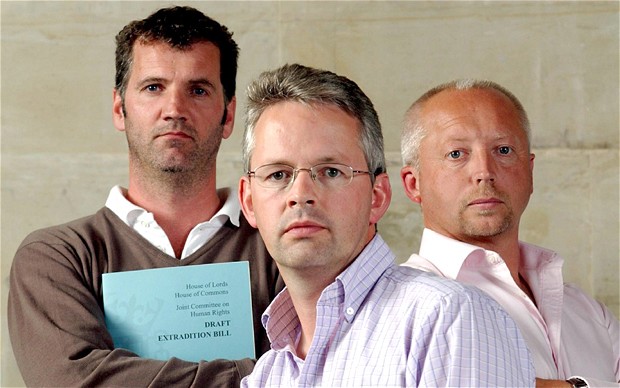

Well, in the case of David Bermingham — one of the three former London-based National Westminster Bank PLC bankers dubbed the “NatWest Three” in the lexicon of Enron criminal cases — he sits for this interesting interview with the Chronicle’s Tom Fowler.

Although he does not reveal how he and his co-defendants intend to defend against the prosecution, Bermingham tells the story of how he and his NatWest colleagues — Gary Mulgrew and Giles Darby — voluntarily went to the UK equivalent of the SEC in November 2001 upon learning through news reports that a transaction in which they and NatWest Bank were involved had become part of the fraud investigation of former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow and his right-hand man, Michael Kopper.

Subsequently, the UK authorities passed along the information provided to them by Bermingham and his mates to the SEC and, the next thing you know, Bermingham, Mulgrew and Darby are the subject of a criminal complaint in Houston.

No US investigator contacted Bermingham, Mulgrew or Darby to get their side of the story before firing off the criminal complaint against them, but — as Bermingham notes — the Enron Task Force probably viewed the three bankers as pawns in their effort to put pressure on Fastow. After Fastow copped a plea, the Task Force was stuck with its dubious decision to prosecute the three UK citizens.

Although not well-reported in the press yet, the case against the NatWest Three is fairly straightforward, at least as Enron-related criminal cases go.

The Task Force alleges that the three defrauded their former employer by conspiring with Fastow and Kopper to underpay NatWest for its interest in an entity named Swap Sub, an affiliate of LJM1, the Fastow/Kopper-managed special purpose entity that was created in 1999 to hedge Enron’s valuable but highly volatile interest in a technology company called Rhythms.

Fastow arranged to have an entity called Southhampton that was owned by his family, Kopper and several other Fastow underlings at Enron (including Ben Glisan) buy NatWest’s interest in Swap Sub in March, 2000 for $1 million, which was substantially more than NatWest had that interest valued at the time.

After NatWest sold out, Fastow sold a portion of the old NatWest interest in Swap Sub through Southhampton to the three bankers personally for $250,000. About a month and a half later, Fastow and Kopper arranged to have Enron and Swap Sub unwind the hedge on the Rhythms stock, which resulted in Enron purchasing a large chunk of Enron stock from Swap Sub. The NatWest Three’s net share of the Enron stock sales proceeds was $7.3 million.

In short, the Task Force alleges that the NatWest Three’s making $7.3 million on an investment of $250,000 a month and a half earlier violates the “too good to be true” rule.

Presumably, Fastow and Kopper are prepared to testify that the NatWest Three knew that Fastow and Kopper had arranged with Enron to unwind the hedge on Rhythms stock with Swap Sub, knew that such unwinding would make Swap Sub worth much more than NatWest had it valued at the time, and that neither Fastow nor the NatWest Three disclosed the situation to NatWest before the bank sold its interest in Swap Sub to Southhampton for a measly $1 million.

For their part, Bermingham, Mulgrew and Darby contend that they knew nothing about Fastow and Kopper’s plan to unwind the Rhythms hedge with Enron, that the $1 million price that Southhampton paid for NatWest’s interest in Swap Sub was substantially more than it was worth at the time, that the $250,000 price they paid for an interest in Swap Sub was similarly reasonable given the risk of the investment, and that they were as pleasantly surprised as anyone on the big return on their investment when Enron and Swap Sub unwound the hedge a month and a half later (remember, all this took place before the bursting of the stock market bubble on tech stocks).

Interestingly, despite the fact that all of the foregoing information has been well-known to NatWest for several years now, the bank did not pursue either a civil case or criminal prosecution of the NatWest Three in the UK.

By the way, colorful Houston-based criminal defense attorney Dan Cogdell, who successfully defended former Enron in-house accountant Sheila Kahanek in the Nigerian Barge case, is defending Bermingham. Cogdell’s involvement ratchets up the entertainment value of any case, so stay tuned.

Sending bad messages

It’s hard to imagine that the federal government could have sent worse signals to foreign investors in US markets and businesses than the ones that it sent over the past week.

First, there was the latest news about the NatWest Three, the three UK bankers who had the misfortune of making an investment in one of Enron’s special purpose entities controlled by former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow and his right-hand man in crime, Michael Kopper. Remarkably, the only reason that the NatWest Three were spared from the Enron Task Force demanding their incarceration in Houston’s downtown Federal Detention Center pending their trial was the intervention of UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, who assured an angered British Parliament a week ago that the bankers would be released on bail.

Nevertheless, even Blair’s intervention didn’t stop the Task Force from demanding that the bankers remain in the US pending their trial (despite the fact that the three offered to waive extradition for trial) and that the three friends live apart and not talk to each other about their case unless their counsel is present. Unbelievably, the federal magistrate who adjudicated the bankers’ bail motion accepted the Task Force’s ludicrous “live seperately” and “no-talk” demands, which means that three UK friends in a foreign land must live alone and cannot talk freely with each other while preparing their joint defense in an extraordinarily unfriendly venue. In the meantime, their only known accusers — admitted felons and liars Fastow and Kopper — have no such restriction in hobnobbing with each other and continue to live comfortably in their expensive Houston homes.

Do we really need this?

This NY Times article reports on the latest international reaction to the US Justice Department’s over-the-top crackdown on internet gambling:

This NY Times article reports on the latest international reaction to the US Justice Department’s over-the-top crackdown on internet gambling:

The World Trade Organization set up a panel on Wednesday to investigate whether United States restrictions on Internet gambling comply with international trade rules.

The Caribbean country of Antigua and Barbuda asked the W.T.O. to set up the panel after consultations with the United States failed to yield a solution to a dispute over whether Washington should drop prohibitions on Americans placing bets in online casinos.

A previous W.T.O. ruling said that some United States laws were in line with international commerce rules, but others were not. ìThe United States has been busy passing legislation that is directly and unequivocally contrary to the ruling,î Antigua told a meeting of the W.T.O.ís dispute settlement body.

The nation contends that the United States has taken no measures to comply with the recommendations and rulings of the dispute settlement body, Antigua said.

Let me get this straight. A supposedly free-trade and business-friendly GOP administration is risking World Trade Organization sanctions over criminalization — as opposed to regulation — of internet gambling?

What’s that criminal charge again?

One big problem with the federal government’s criminal case against the defendants in the KPMG tax shelter case is that neither the defendants nor any of their clients engaged in any affirmative act of evasion, such as keeping false accounting books or literally hiding income so that the IRS could not find it. Rather, each taxpayer claimed losses on the taxpayer’s return in accordance with a literal application of the tax law and then, as often happens, the IRS challenged the claims. KPMG’s clients needed KPMG’s opinion regarding the validity of the tax shelters to protect themselves against civil penalties the IRS might try to impose as a result of a challenge to the tax returns, but they did not need the KPMG opinions to file the tax returns claiming the losses. Thus, the KPMG opinion had not bearing on the propriety of filing a tax return and is irrelevant to the crime of tax evasion.

One big problem with the federal government’s criminal case against the defendants in the KPMG tax shelter case is that neither the defendants nor any of their clients engaged in any affirmative act of evasion, such as keeping false accounting books or literally hiding income so that the IRS could not find it. Rather, each taxpayer claimed losses on the taxpayer’s return in accordance with a literal application of the tax law and then, as often happens, the IRS challenged the claims. KPMG’s clients needed KPMG’s opinion regarding the validity of the tax shelters to protect themselves against civil penalties the IRS might try to impose as a result of a challenge to the tax returns, but they did not need the KPMG opinions to file the tax returns claiming the losses. Thus, the KPMG opinion had not bearing on the propriety of filing a tax return and is irrelevant to the crime of tax evasion.

To get around that problem, federal prosecutors came up with the second crime of so-called tax perjury, which involves a demonstrable lie asserted in a tax return or some other document that is submitted to the IRS under penalty of perjury. However, the tax perjury case against the accountants is flimsy at best. During the audit of the KPMG clients’ returns, the KPMG clients contended that they had a business purpose sufficient to meet the IRS standard for avoiding civil penalties and then produced KPMG opinion, which is not submitted under penalty of perjury. Thus, best case for the prosecution is that the taxpayers and KPMG may have been disingenous, but that hardly renders perjurious the submission of a tax return that was factually correct.

Now, it appears that at least some of those tax returns were not even misleading. According to this NY Times article, US District Judge T. John Ward of the Eastern District of Texas ruled earlier this week in a civil case that one of the KPMG tax shelters that is at the center of the KPMG tax shelter case is essentially legitimate.

What is the Justice Department’s justification for criminalizing such conduct? According to the article, “prosecutors in the KPMG case have indicated that they will argue that the shelter itself was technically valid, but that the way the defendants carried it out was not.”

As this Wall Street Journal ($) editorial opines today, there is a serious shortage of adult supervision in the US Department of Justice these days.

More on the latest prosecutorial abuse

Following on the latest example of out-of-control federal prosecutors, Cato Institute’s Radley Balko has the best line of the day in responding to one of the vapid rationalizations for Congress’ jihad against online betting — “we have to protect our chidren from such evils:”

Following on the latest example of out-of-control federal prosecutors, Cato Institute’s Radley Balko has the best line of the day in responding to one of the vapid rationalizations for Congress’ jihad against online betting — “we have to protect our chidren from such evils:”

“The people who are pushing this ban in Congress . . . try to argue these sites prey on children, which is totally ridiculous,” [Balko] said. “If your kid has access to your checking account or credit card and is making transfers to off-shore accounts across the world, Internet gambling is the least of your worries.”

Balko has more on the absurdity of all this here.