This NY Times article tells the fascinating story about the assassination of President James A Garfield in 1881 an exhibit commemorating the 125th anniversary of Garfield’s assassination at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

This NY Times article tells the fascinating story about the assassination of President James A Garfield in 1881 an exhibit commemorating the 125th anniversary of Garfield’s assassination at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

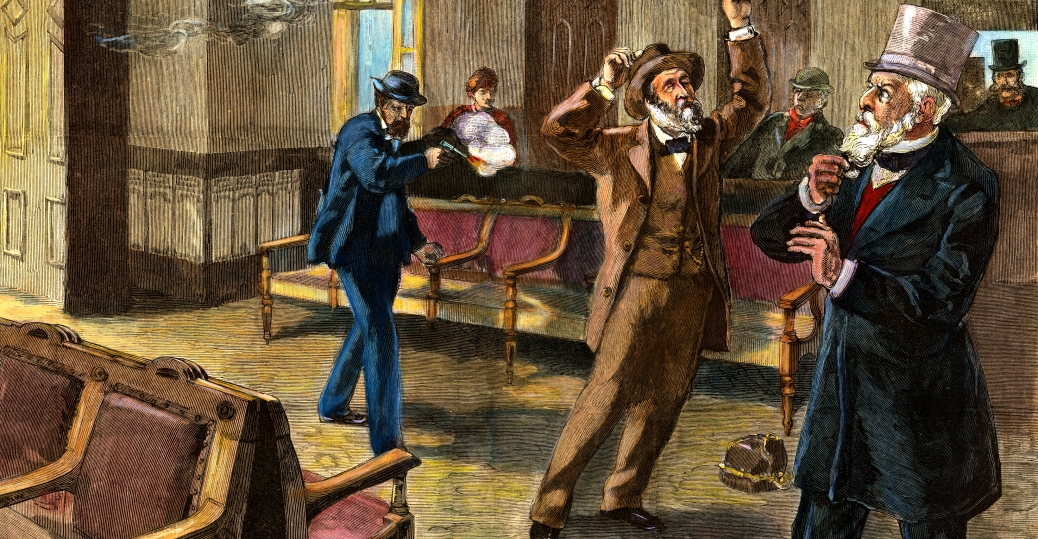

President Garfield was shot in Washington by a disgruntled federal job-seeker, Charles J. Guiteau, who made his move while Garfield was waiting for a train. What is not as well-known is that neither of the shots that hit Garfield should have fatal even by the more primitive medical standards of the 1880’s.

As my late father once observed to me in a discussion of Presidential assassinations, “Garfield’s assassin just shot him. Garfield’s doctors killed him.”

The Times article reminds me of another interesting medical case that Dr. Donald J. DiPette, chair of the Department of Internal Medicine at Texas A&M University Medical School, presented earlier this year during the annual Walter M. Kirkendall Lecture that the University of Texas Medical School conducts in honor of my father.

Dr. DiPette’s lecture was about how advances in clinical research on hypertension had contributed to our understanding and knowledge of related chronic illness. He used a case study of a man in his mid-50’s in the late 1930’s who was showing signs of acute hypertension as an example of how that understanding can change the world.

The negative impact of hypertension on an individual’s health was not well-understood in the late 1930’s and 40’s. Dr. DiPette showed how the patient’s health in the case study deteriorated at an accelerated rate as his blood pressure readings increased markedly from 1937 to 1945. One evening in early 1940, the subject in the study fainted at the dinner table. The patient’s doctors at the time were unsure why.

By 1945, the patient — who was still working in an important and high-pressure job — had blood pressure that was off the charts and was experiencing a combination of associated medical problems that would have landed him in a hospital these days.

Nevertheless, the patient continued to work and, a couple of months after a particularly important work-related meeting, the patient died of a massive stroke.

Most times, the subjects of medical case studies are anonymous. But at the end of his lecture, Dr. DiPette revealed the name of the subject of this particular case study — President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Dr. DiPette’s point was that President Roosevelt’s acute hypertension clearly affected his performance. Our lack of knowledge about hypertension in 1945 — which finally began to be better understood in the decade after FDR’s death — changed the course of the 20th century. That “important work-related meeting” that Dr. DiPette referred to was the Yalta Conference of early February 1945 that doomed Eastern Europe to over a generation of tyranny.

Remember that the next time you hear someone complain about the cost of advancing medical research.

Nice post Tom.

Speaking of medical progress…while playing some basketball tonight, one of my teammates needed some food for glucose to offset the insulin he has to take prior to playing ball. (One night he had an ugly hyperglycemia reaction).

I happen to be by a phone so I dialed up my wife, the diabetes nurse at the Univ of Iowa’s Family Care Center. “What was the name of that new drug for diabetes?î I asked, since this is not my area of expertise.

Turns out the new drug is an injectable for Type 2 diabetes, or those who have diabetes due to poor diet and weight gain.

“Well any new developments for Type 1 diabetes”, I asked? (Type 1, being the type where the pancreas is not putting out enough insulin). “Stem Cell Research” she said.

This is my point. Our Govt has politicized a good avenue of scientific inquiry, one that may offer hope for disorders like diabetes, and Parkinson Disease.

At this point, medicine may not have killed the leader of the Govt, but the leader of the Govt may have killed (new) medicine.

Tom,

Thank you for sharing the New York Times article about the Garfield exhibit at the National Museum of Health and Medicine. But everyone needs to hurry if they’d like to see it, because it is closing on Sept. 19, 2006.

Steven Solomon,

Public Affairs Officer,

National Museum of Health and Medicine,

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology,

6900 Georgia Avenue at Elder Street, NW

Washington, D.C. 20307